SNOOPY

SNOOPYThe Assassination of Apollinaire

Alessandro Mercuri __ February 18, 2013

The first issue of the gazette Le Mercure Galant—or Le Mercure Galant containing many true stories, and everything that happened before the 1st of January 1672 until the departure of the King—was published on the 1st of January 1672. It was renamed Le Mercure de France in 1724.

On March 17th 1916, during the First World War, in a French trench on the front line, Guillaume Apollinaire read an article about Edgar Poe by Walt Whitman in issue 426 of Le Mercure de France, published the day before. The American Poet wrote: ‘In a dream I once had, I saw a vessel on the sea, at midnight, in a storm. (...) with torn sails and broken spars through the wild sleet and winds and waves of the night. On the deck was a slender, slight, beautiful figure, a dim man, apparently enjoying all the terror, the murk, and the dislocation of which he was the centre and the victim. That figure of my lurid dream might stand for Edgar Poe, his spirit, his fortunes, and his poems—themselves all lurid dreams.’ An enemy bullet streaked through the sky, descended in a curve before dropping right into the trench. The nocturnal dream of Walt Whitman was erased amid the din of a violent explosion. Blood, bone and brain splinters spurted onto the gazette. Guillaume Apollinaire was wounded in the head by German shrapnel. Was the soldier-poet wearing his steel helmet during the blast? Could the winged helmet of Mercury, emblem of the publishing house, have saved the author of The Poet Assassinated? After dipping his index finger into the congealed texture of his nervous system, Apollinaire held his finger to his lips and cried: “What a taste…what a strange taste… the soul is.” Then, he lost consciousness. Sent back to Paris, he was trepanned on the 10th of May 1916.

In 2002, in homage to the poet, the publishing house Mercure de France created a series of books entitled “The Taste of”. Fascinated with alphabetical order and more importantly by the letter B, which follows so closely the A of Apollinaire, we can quote among others: The Taste of Bali, The Taste of Barcelona, The Taste of Belgrade, Of Berlin, Of Beirut, Of Burma, Of Bordeaux, of Brittany, Of Brussels, Of Bucharest, Of Budapest and Of Buenos Aires… Are these travel guides? No, far from it. Behind the postcard-like and cheap aesthetic of the covers, hides actually great literature with a big ‘L’ and two small touristic ‘Ts’, LiTeraTure.

On the 11th of October 2012, the Mercure de France released The Taste of Switzerland anthology. This could force Saint Eligius and Saint Matthew, patron saints of watchmakers, bankers and accountants, to turn in their graves. And we can hear their words uttered in a sepulchral voice: Oh you Holy Ghost, Sacred Phantom and Holy Spirit tell us: “Aren’t there any values nowadays but those of the market? Any paradises but fiscal ones? Any speculations but financial ones and any freedoms but capitalist ones?”

“The Taste of Switzerland” offers amongst others texts by Goethe, Hugo, Louis Aragon, Lord Byron, Blaise Cendrars and Jules César about the Helvetian paradise. Let us leave the task of presenting the book to the publisher: “On the 26th of February 1767, Voltaire addressed a letter to James Marriott, counsel for the prosecution: “One half of Switzerland is hell, and the other half is paradise”. Travel writing, glaciological and alpine adventures, tales of conquered summits, unusual encounters, picturesque stories, humorous viewpoints of a nation not as simple as it seems: with either benevolent eyes or scathing criticism, the Helvetian cauldron has kept the literary world boiling for several centuries.” The bubbling up of the Helvetian letters is reminiscent of other thrills.

Shortly before the war, the author of The Eleven Thousand Rods released the works of the Marquis de Sade in the “Collection des Classiques Galants”. The 120 days of Sodom were not included but if they had, here is what could have been read from “The hundred and fifty murderous passions, or those belonging to the fourth class”: A red-hot cast-iron bell is placed on her head so that her brain slowly melts and her head slowly grills.” Bombardment in the sky, explosion of shells, incandescent splinters, fire and powder penetrating the brain. Trepanned, weakened by his wound, the poet died of Spanish influenza on the 9th of November 1918. He was buried on the day of the Armistice. As his coffin passed by, so the legend goes, Parisians burst out in a cheerful cry “Death to Guillaume!” What was this fatal ire of the people of Paris against poetry? “Death to Guillaume!” Why ask for the death of someone who was already dead? To resuscitate him? Dada was born. “Death to Guillaume!” Is it only Guillaume the Apollinairian, Orphic and Apollonian, half-brother of the Greek Hermes, Roman Mercury... of France? In truth, this exhortation to murder, “Death to Guillaume!”, is aimed at another Guillaume, not Apollinaire, born Wilhelm Albert Wlodzimierz Apolinary of Kostrowicki, but at Fréderic Guillaume Victor Albert of Hohenzollern, William II, Emperor of Germany and the last king of Prussia.

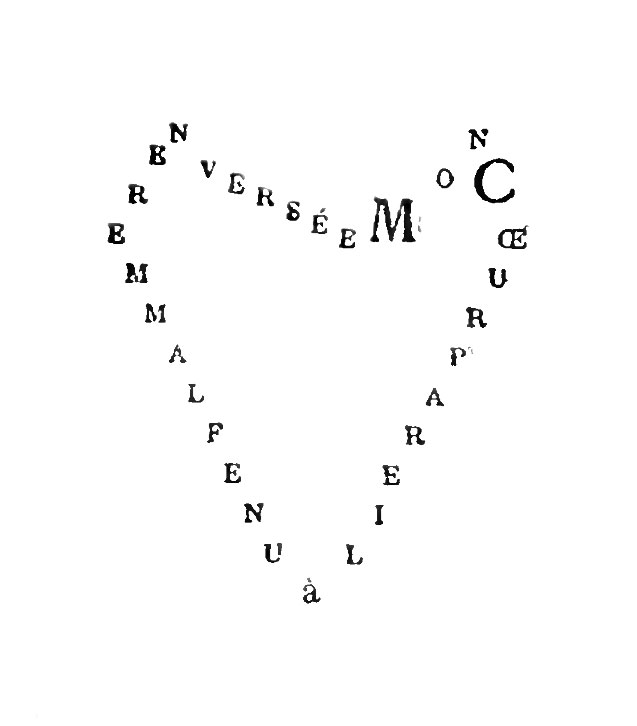

Then the funeral procession continued its way towards the last resting place of the poet, a tomb soon to be surmounted by a lugubrious menhir designed by Picasso. On the gravestone, a heart-shaped calligram can be read: “My heart like an upside-down flame”. The collection Calligrams, subtitled Poems of Peace and War appeared in the same year of 1918, published by the.... Mercure de France.

“My heart like an upside-down flame”

The eternal flame under the Arc De Triomphe

On the 11th of November, at 6pm, the minister of War, M. Maginot, lights the flame which should not go out again (with the help of a tow placed at the end of a foil).

Photo J. Clair-Guyot (L'Illustration, November 17th 1923)

Translated from the French by Paul Stubbs & Blandine Longre

TAGS : The Assassination of Apollinaire, Le Mercure Galant, Le Mercure de France, First World War, Guillaume Apollinaire, Walt Whitman, Edgar Poe, winged helmet, Le goût de, Le goût de la Suisse, Goethe, Hugo, Louis Aragon, Lord Byron, Blaise Cendrars, Jules César, Voltaire, Onze Mille Verges, Marquis de Sade, The 120 days of Sodom, Guillaume II, Calligrams

NEXT POST >>