KISS ME DEADLY

KISS ME DEADLYMad(e) in France - Land of Madness by Luc Moullet

Alessandro Mercuri __ November 29, 2011

In The Cinema according to Luc, Luc Moullet explains the following about his latest movie, Land of Madness (La terre de la folie, 2009): “Madness often leads to murder. I recount how my cousin had killed the ranger, the mayor and his wife, because the ranger had moved his goat 10 meters. Well, three people died. Yet if I tell you this story, it might make you laugh because it's so absurd and it inevitably has comic value. I often quote the example of the mad Emperor Caligula, who had many people killed and who had appointed his horse proconsul. The lunatic is actually a jester, whose role is to make people laugh. At the same time, a lunatic is often a murderer. So the two go together. Murders without motive always seem completely irrational. Therefore it is funny but also deadly.”

Allergic to anything too serious, miles away from gravity and pomposity, Luc Moullet is often described as an auteur with a dry sense of humor. The distinctiveness of his work is revealed through irony, black humor, a sense of derision and of the absurd. Opening credits. The title appears in capital letters on a black background:

LA TERRE DE LA FOLIE

DE LUC MOULLET

As suggested by the title, the movie as a whole will be twofold and equivocal, ambiguous and polysemic. Indeed, the French preposition “DE” between “FOLIE” and “LUC” can be interpreted in different ways. It could naturally mean “a film BY Luc Moullet” but also “the land of madness of Luc Moullet”, his own “land of madness” or “the land of his madness”. Then suddenly two gunshots ring out. Probably a hunting rifle. Though the black backdrop will not fill with blood-red splashes like in a B- (or Y- or Z-) horror movie. Cut.

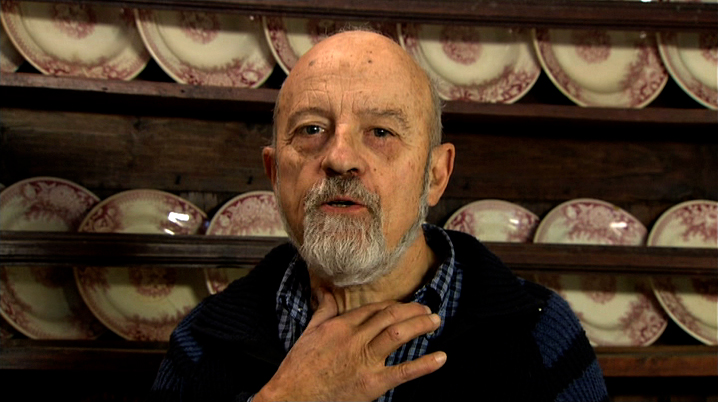

Standing in front of a shelf full of white and mauve earthenware plates and facing the camera, the filmmaker admits: “I’m not such a normal person. I always live on the edges of reality.” Second shot: we see him climbing a ladder leant on the doorframe of an opened attic hatch; then addressing the viewers: “Come and see my film collection.” And a few moments later: “I think I had been bewildered by the paranoia of my father, who had fervently supported Stalin, then Hitler and the post-war neo-Nazis and finally Enver Hodja, Mitterrand and Mao (…) My father had been deeply disturbed by the behaviour of some of his relatives, who were from the Southern Alps.” The tone is set. The filmmaker will play different roles; as narrator-writer-actor-character, he addresses us from his own film, a simultaneously intimist, scientific and zany documentary movie: intimist because the audience is faced with personal accounts of crimes, of all sorts of gratuitous or villainous murders, of suicides and murder attempts; scientific because Luc Moullet adopts an ethnological, geographical and anthropological approach to the criminal phenomenon; and zany because from start to finish the movie reveals a tension between tragedy and comedy. Laughter is not just a way to escape the macabre aspect of the executions. It constitutes the underlying thread of the bloody stories related throughout the film. The singularity of a crime closely linked to madness lies in its absence of motive, reason or explanation. Absurdity opens up a door where laughter and nothingness converge.

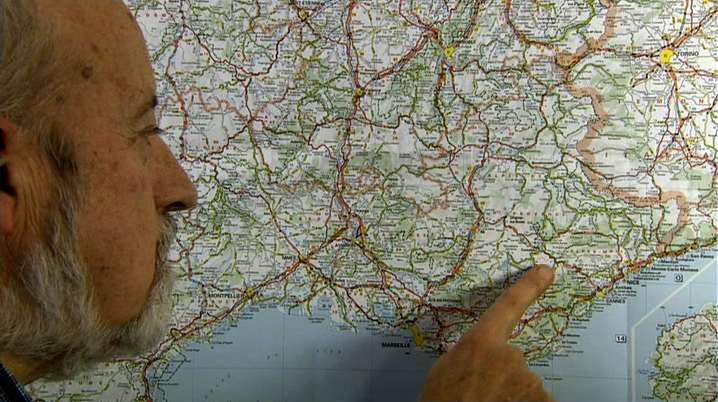

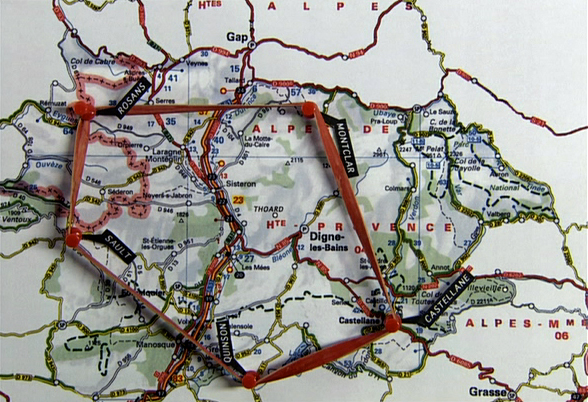

The film is set in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. On a map of the area, Luc Moullet draws, with a rubber band, a sort of pentagon of madness, the imaginary figure of the map he will use to investigate the territory. As the landscapes, the towns, the villages pass by and the stories progress, the audience is confronted with a flood of violence. Events occurred in the places marked on the map. Yet only memories remain. In the same way as the police cordon off crime scenes and order bystanders to “move along, there’s nothing to see”, the film stands out because of its absence of images. There’s almost nothing to see. Crime remains invisible, the setting empty, bucolic and pastoral, landscapes seemingly calm and peaceful. Yet, little by little, it gives nature a disturbing edge. Murders have sprung up from desolate landscapes in the same way as the living dead from a horror movie spring up in an abandoned graveyard. Here, fresh air and bucolic love between shepherds and shepherdesses have disappeared, to be replaced by neighborhood or territorial quarrels—in short, a bloody pastoral. As one of the participants in the movie puts it: “a love story lasts two or three years, a passionate affair six months, but hate can last a century (…) hate makes life endurable.” And in these deserted regions, since there are no motives, no evidence and no witnesses, it is natural to blame nature, landscapes and solitude. The wind drives people to madness. The earth and the rocks make men bitter, brutal and harsh. Gilda, the femme fatale with her long black satiny gloves, already used to sing:

They said that Mother Nature

Was up to her old tricks

That's the story that went around

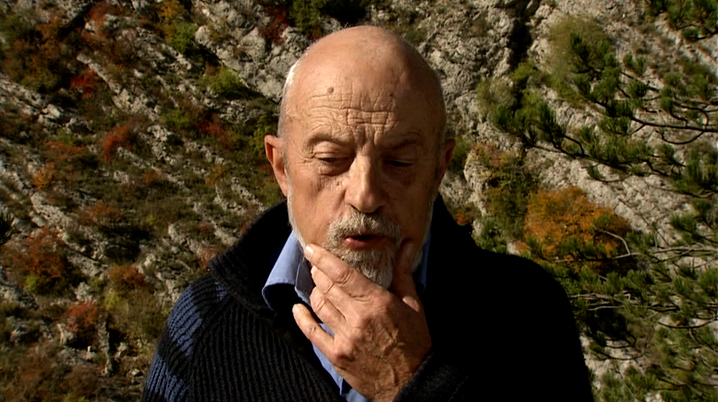

Land of Madness is a minimalist, conceptual film noir in which the only remnants of the crimes would be memories and landscapes. Luc Moullet is well-known for his propensity to film nature, rocks and badlands (or roubines). The role played by landscapes and the reality of rural life (or terroir) is a constant visual and narrative dimension in his work, which can only be compared with western movies, so that we could say that these badlands represent what Monument Valley embodied for John Ford, not only as a mere landscape but also as a symbolic place where events originate.

The filmmaker plays with the norms of cinema and genre cinema, while distorting the norms of the investigative documentary. The reconstructed scenes which punctuate the accounts of the crimes seem to ridicule the voyeuristic and factual obsession of journalism. During the film, a tension thus arises between hearing and seeing, between what is told, shown or reconstructed. When witnesses appearing in the movie ask to remain anonymous, it is their names which are blurred, not their faces, the filmmaker then outwitting the audience’s expectations. Luc Moullet plays also with the deliberately and flatly illustrative aspect of the images or of the visual sequences which consolidate the subject matter. The vision of a burning mannequin on top of a hill overlooking the city, in place of a woman who set fire to herself, is a truly weird postcard from Provence. Or take the account of a suicide shown as if in a sensationalist news TV program: a car speeds along a cliff-top road, veers off the bend and plunges into the depths below—a scene shot which uses subjective camera from the inside of the vehicle as it crashes into the ravine. The reconstruction is not only fictitious. It is also part of the criminal investigation conducted by the scientific police. This reconstructed scene is the apex of artifice: a life-size staging in which the person presumed guilty re-plays the murder, like an actor who would play his own character once the crime has actually been committed. Reconstruction is a cinematographic fantasy: that of a confession no longer made through words but rather through images in motion.

Land of Madness is a documentary film which playfully pretends to be a special news report. Like any other cinematographic work of art, this movie questions its own means of expression as a visual and narrative form. Cinematographic fiction is based on an implied and unconscious pact of confidence between director and audience. Cinematographic dream or fiction must be experienced as if reality. This secret agreement concluded in the darkness of the movie theater is generally called “the willing suspension of disbelief”. Land of Madness may not be a fiction introducing imaginary events but a documentary recounting real crimes, yet one of its most disturbing aspects lies in the questioning of the suspension of disbelief itself. The realistic dimension of the documentary generates fictitious effects, encouraging the audience to believe in implausible stories which are nonetheless true. Let’s take for instance the account of a police investigator describing a macabre discovery, that of a heavy bin bag thrown into a river bed: “At first, the policemen did not really pay attention to it because they thought it contained the limbs of mannequins, the kind you find in shops. It was only when I was called in that I realized that they were actually human remains.” In a comical way, and in spite of ourselves, we could almost think ourselves in the position of the one insane. For madness lies also in the impossibility of distinguishing truth from falsehood, a dismembered mannequin from a corpse cut into pieces, the real from the unreal. Corneille had indeed entitled one of his plays The Comical Illusion.

Direct or indirect witnesses of the crimes tell us stories. “Telling stories” is a famously ambivalent phrase. The mere fact of the telling transforms facts into stories. In quantum mechanics, observation influences the observed system. In a film, the oral account influences the meaning of the fictitious story. Once upon a time there was a true or invented story—the truth or make-believe? And what can we infer from the unexpected intervention of the filmmaker in the middle of the movie, when he explains: “The witness failed to appear at the last moment. He got scared. So that I’m the one who’s going to talk to you. I do apologize.”? Land of madness is not a fake documentary, nor a mockumentary, nor a hoax. Yet it makes use of formal devices which are usually employed in fictitious stories. The accounts of murders without motives, hence implausible, convey a weird and disturbing impression of unreality. This impression takes on a hallucinatory aspect during the recurring dialogues between the filmmaker and a woman suffering from psychiatric disorder, who is also affected by echolalia, a spontaneous tendency to repeat words, like an echo: “In Normandy, where it rains a lot, everything is green. But here, it doesn’t rain much. Stones are what grow easily here. People were poor peasants, that’s why they were wary, selfish and miserly, because it was necessary. If they wanted to survive, they had to cling to life and be suspicious of their own neighbors…” she says. Then bis repetita: she starts repeating her own words. This pathology of repetition turns into a comic and an aesthetic of redundancy, as revealed by the laboriously illustrative aspect of these images (visually repeating what we have just heard) or of the other scenes in which the tragic events are reconstructed ad minima.

Evil blows over the region. The wind drives people to madness. Madness remains as unfathomable as the wind beating over the plain. The great invisible spirit strikes at the very heart of the film. “On the last day of the shooting, a new tragedy occurred”, explains the filmmaker. The landlady of a bar has just been savagely bludgeoned to death by a mentally deranged man with a bottle. Madness, the subject of the movie, pours into the documentary uninvited. Hence, in one out of the many zany sequences of the movie, the filmmaker simulates and reconstructs his own aborted suicide attempt from the height of a bridge. This failure is followed by the word “Intermission” on a black background, accompanied by the notes of a violin. Madness is contagious, contaminating, truly alive, a live phenomenon within the documentary. Madness has definitively seized control of the movie. Ultimate sequence: on the crest of a mountain, a couple quarrels. The filmmaker’s wife reproaches her husband for his biased explanations of this local madness. The filmmaker has already explained that the Chernobyl cloud had had a criminogenic impact. Antonietta Pizzorno Moullet, irritated, replies: “Radiation doesn’t trigger madness”. And Luc Moullet answers: “It doesn’t, yet it’s a continuous process.” Never has such a cursed territory circumscribed by its own madness been so hilarious.

We explore it as if watching a zombie film, flitting between anxiety, terror and uncontrollable giggles. “Madness is often linked to the way solitude can grip you. Sometimes, there’s only one inhabitant per square meter. So that you can kill without being seen. Besides, the frequency of the murders, committed with impunity, somehow encourages others.” Anyone can fall victim. To fiction or to madness? For the land of madness is also cultivated in a pot. “In this place, there is a culture of murder and insanity which can even affect some descendants who’ve never even gone to the Alps”. In 1955 Orson Welles, who also made F for Fake, started to shoot an unfinished documentary about one of the most famous murders committed in this area: the Dominici case, which is also dealt with at length in Land of Madness. F for Fake, indeed, but above all F for Film, for Fiction, for Folly.

Considered by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Marie Straub as Courteline reinterpreted by Brecht or as the heir of both Luis Buñuel and Jacques Tati, Luc Moullet could also be seen as an explosive blend between Robert Bresson, Ed Wood and Tex Avery. To paraphrase Stendhal, we could say that with Land of Madness, “a film is a mirror being carried along a road”, a white rabbit worried about being too late clinging to it. In this mirror, Luc Moullet, who is fond of walking, mountain climbing and trekking, paces up and down the inverse image and the unreachable blind spots of the landscape and the psyche.

Alessandro Mercuri

(Translated from the French by Blandine Longre and Paul Stubbs)

Photograms : La terre de la folie