SNOOPY

SNOOPYThe adventures of Jesús Maria Veronica in Holyhood

Alessandro Mercuri __ November 30, 2011

Winter 1531, Florence, Italy

Michelangelo has just completed a series of preparatory studies. The first rough sketches are drawn on paper. Their dimension: about 30 centimeters in length and 30 in width. The final work will be a 17 meters high and 13 meters wide Vatican fresco: a change in scale and perspective so that the trumpets of the Last Judgment can resound.

Winter 1531, Mexico City, Mexico

On top of Mount Tepeyac, the Virgin Mary, “dazzling with light” and as white as snow, appears to an Aztec Indian, a shepherd converted in 1525 by the Spanish conquistadors. His name: Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin. The Virgin asks him to erect a church on this very spot. Back in town, Juan Diego goes to see the Franciscan bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga, so as to inform him of what he has just seen and heard. The prelate, the first bishop of New Spain, finds it hard to believe. On the same evening, Juan Diego, despondent, looks up to the stars. A cloud of astral dust shines in the firmament. It resembles the Milky Way. “Is it possible to be a believer and not believe?” wonders the shepherd. It sounds like The Milky Way, not the one in the sky, but Luis Buñuel’s movie, with Alain de Cuny or Fernando Rey in the role of Juan de Zumárraga. Juan de Zumárraga, a moderate, enlightened and humanist ecclesiastic, had previously been a judge in the Spanish Inquisition in the Kingdom of Castile. It is said that during the witch trials, he was one of the few to consider that the possessed women were victims of hallucinations rather than under the domination of the Devil. The bishop, being sceptical, asks Juan Diego, the presumed witness, to bring back some miraculous evidence of the mysterious apparition—this image of the divine appearing among the living. What better proof indeed of an image than another representation, as confirmed by the phrase “an image is worth a thousand words”?

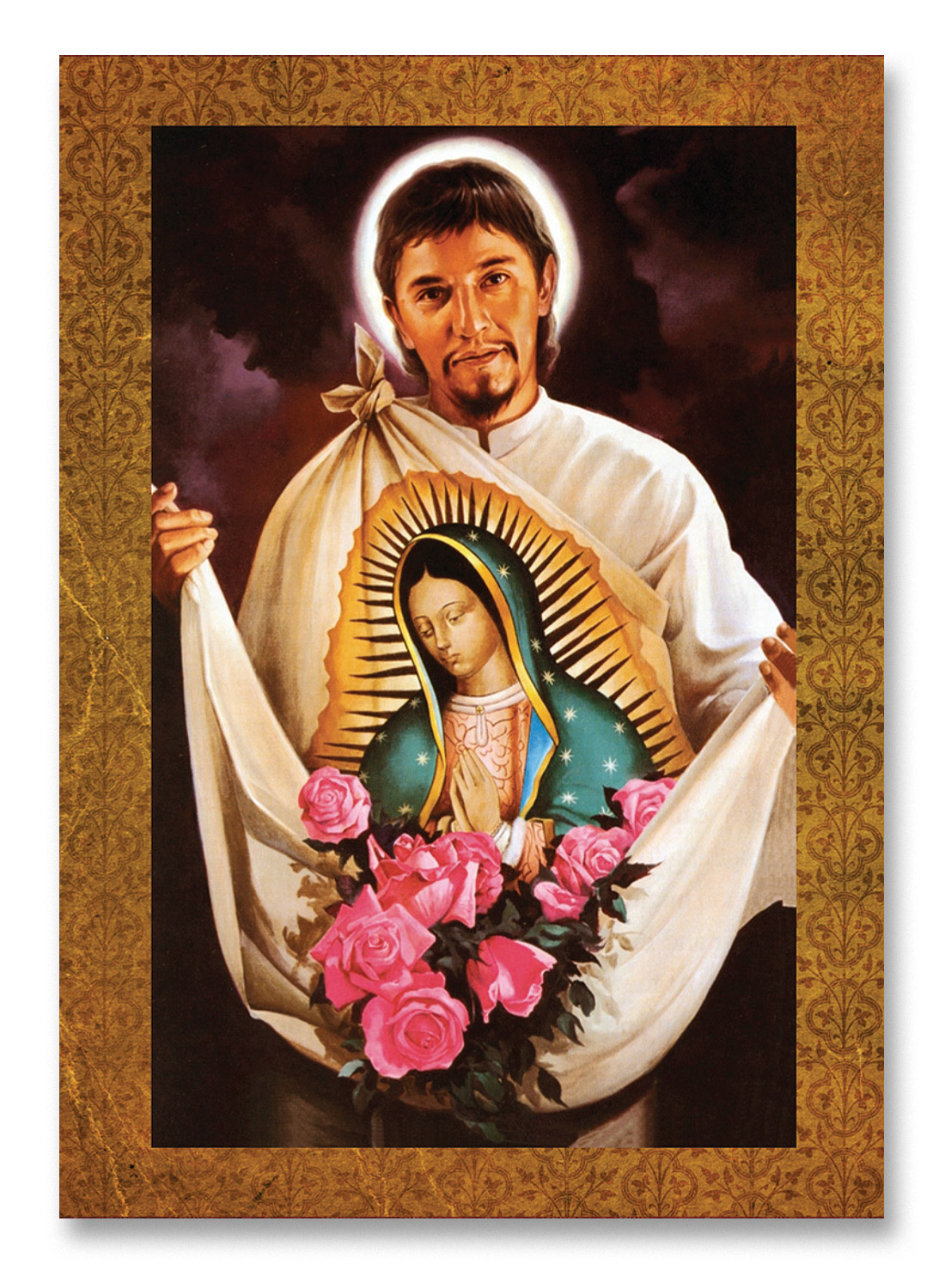

Juan Diego goes back up onto the heights of the mount and half a millennium later, in 2002, the one who saw is canonized by Pope John Paul II. Has the Aztec shepherd become Saint Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin for the only reason that he has witnessed a vision? Seeing and painting are two different things altogether. But as if by miracle, the Mexican apparition of the Virgin links up both processes: the vision and the representation. Mary asks the new believer to pick up roses. O sweet wintery miracle of the flowers covered in snow. The Indian then goes to reveal to the bishop his treasure of petals, sepals, stigmata and pistils. When he opens his coat, the virginal flowers glide down the garment to unveil an icon of the Virgin printed on the material. The next morning, the first stone is laid. The construction of the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe begins as early as 1531 on the very spot of the apparition. The shrine is completed in 1709. In 1921, close to the altar, an exterminating angel keeps watch: an anti-clerical activist hides a bomb in a vase of roses. The bomb explodes. The Basilica is partly destroyed but the holy image remains immaculate. In the new Basilica, rebuilt in 1974, more than 20 million pilgrims pray every year in front of the miraculously intact and miraculous icon, probably the most famous and popular religious representation or holy image in existence.

Juan Diego - Merry Christmas Series - Catholic Extension card

Our Lady of Guadalupe – Basilica of Guadalupe

photo by Hernán García Crespo

What is the nature of this image? Pictorial, hyper-realistic, photorealistic, photosensitive or simply divine? The mixed technique (rose and divine pigments on a tilma made of linen?) remains unknown, yet it is certain that it was not painted by the hand of man, but is a representation achieved without any human involvement, a manifestation of the Spirit. The image is thus said to be an acheiropoieton, etymologically “made without hands”. In 2009, during an official trip to Mexico, Hillary Clinton, Secretary of State of President Barrack Obama, visited the new Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, where she was received by His Eminence Diego Monroy. On behalf of the American people, she laid a bouquet of white flowers at the feet of the Virgin. An excerpt from the conversation as reported by the CNA, The Catholic News Agency:

— Who painted it?

asked the former First Lady,

her gaping eyes staring deep

into those of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

— God!

replied the episcopal vicar.

— Through the night with a light from above,

From the mountains, to the prairies,

To the oceans, white with foam,

God bless America (...)

sings on Beyoncé

in her sweet sensual voice.

An anonymous oil painting on canvas from the 18th century portrays God painting the Virgin of Guadalupe on a linen canvas hanging in the clouds, held aloft by angels and cherubs. God the father sits, a brush in his right hand and a palette in the left. Instead of the traditional multi-colored flecks of paint, the palette is covered with roses—exquisite detail. Popular religious imagery and holy images are sometimes so profoundly naive and poetically profound. Some of them insist on the iconic dimension of the wonderful meeting. The Blessed Virgin appears to Juan Diego in the exact way that she is revealed by the roses. Aesthetically speaking, the immaterial apparition in the air and the material apparition printed on the linen coat coincide. Both are visually and pictorially identical. But what is the nature of Juan Diego’s vision? Did he see the Virgin as a flesh and blood being or the essence, i.e. the spiritual image of her apparition? And could the apparition of the Virgin already be an image in itself?

“God painting the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

Anonymous author, 18th century.

On top of Mount Tepeyac, it is not the Virgin personified in a flesh and blood body who allows herself to be seen, but the Madonna as an image incarnate, elusive and ineffable. Neither a physical body nor a disincarnate image. What has appeared as if by miracle disappears as if by magic. In the Gospel according to the Apparition, we could replace the Word by the Image and declare: In the beginning was the Image… To those who believed in his name… The Image was made flesh. The image becomes incarnate in a spiritual body. A glorious body of light and colors in an oval of divine and golden flames. An imaginal body. A sacred and vibrant image among the improbable and magical roses, blossoming and wintery. As if in a strange trinity, an iconographic equivalence is established between the perception, the apparition and the representation. The Virgin is identical to her own apparition, which is itself equal in every respect to its pictorial image. Not three images but a triple one which is to be seen as one representation: an icon. The aesthetics of the icon creates a distinction between the contents and the form, between the background of golden leaves of the image and the representation of the religious figure. The iconic representation over-signifies the status of the image by insisting on its “imaginal” dimension, that is to say the revelation of an image as detached from any medium, outside any spatial reference, floating in a halo of gold and light.

The identity between the three different moments of the vision also leads to the multiplication of the image. The original acheiropoieton is in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. But its countless copies, reproduced by hand or duplicated in a multitude of formats, abound in numerous churches, like a rosebush in full bloom. How can we tell from one rose to the other? All the Guadalupean representations—the original as well as its copies—are revered in the same way. For the original is already the image of an image: the image of an apparition. The representation as acheiropoieton is the printed apparition of the Virgin Mary. It is true to the original. The original is a copy. COPY HOLY RIGHT. The other copies endlessly reproduce an image which originally was, in itself, already multiplied by two, being the image of an image.

Our Lady of Guadalupe, 1893 – Coat of Arms of Mexico, 1743 – Italian engraving, 1732

What we see when we are awake, with either open or blinking eyes, is only a representation. An image impresses itself on the eye’s interior structure, on the retina lined with photosensitive sensors. To Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, too often caricatured as a den of ignorance, a place of illusions and deceiving appearances, we could oppose the metaphor of the camera oscura, that of the darkroom of the eye—an obscure, moist and aqueous place where all visual processes occur. If everything we see is, by definition, an image, hence the apparition of the Virgin can be interpreted as an archetype of representation. Its “purity” does not lie only in its sacred dimension. The apparition is a “pure image”, which has no other reality than that of being an image. The apparition doubles the image: it projects itself onto the retina in the same way it projects itself miraculously without any medium, except its own photon-pigments when in contact with the air. The only screen of the apparition is the ether. Fictitious, truthfully mendacious, deceitful, hallucinatory, induced, real or miraculous, the Marian apparition is an electro-chemically sacred signal.

On earth, Christians pray to the Blessed Virgin. In Italy, believers pray to the Madonna. The Virgin and child, or Madonna, is not a scriptural reality but a pictorial or sculptural iconographic representation. In the country of Giotto di Bondone and Pier Paolo Pasolini, the term Madonna is used indiscriminately to refer to the Mother of the Child and to signify her representation. Can we separate the Virgin from her child, from her image? Can we make the distinction between Mary as the Mother of God and as a representational reality? Can we talk about a Marian apparition in a theological sense or about a “Madonnal” apparition in the Italo-aesthetic sense of the word?

As revealed by the icon in the Basilica of Our lady of Guadalupe, the representation of the Virgin is an icon painted on a linen coat, not a pseudo-photographic imprint such as the Shroud of Turin or the face of Christ which appeared on Saint Veronica’s veil. Although painted with pigments and not printed with photons, some believers consider the image is a genuine photograph.

According to the official website of “Our lady of Guadalupe – Patroness of the Americas” (www.sancta.org), in 1929, Alfonso Marcue, the official photographer of the Basilica, made a very strange discovery. While developing a photographic enlargement of the face of the icon, he noticed reflections in the eyes of the Mother of God. On the surface of the sacred cornea, the reflection of a bearded man appeared. This is how the religious website describes this illumination: “Initially he did not believe what was before his eyes. How could it be? A bearded man inside of the eyes of the Virgin? After many inspections of many of his black and white photographs he had no doubts and decided to inform the authorities of the Basilica. He was told that time to keep complete silence about the discovery, which he did.” More analyses were conducted along the years. Optical and ophthalmological evidence built up. What could this reflection be but the face of the watcher in the eyes of the watched Virgin? The reflection detected in the divine eye can only be the inverse image of one man, the one who witnessed the apparition on a winter morning in 1531, on top of Mount Tepeyac covered with petals of frozen dew. Is it an illusion? A subliminal optical message? A case of pareidolia, when the eye is deceived into seeing a faulty (para) image (eidos)? Would the eye of the Virgin be like a cloud blossoming in the sly, inviting us to the divination of a bestiary of imaginary shapes?

If the reflection in the eye may make us smile or seem almost laughable, it nevertheless remains an essential perceptive moment of the apparition. In his Treatise on Painting, Leonardo da Vinci writes: “I will not omit to introduce among these precepts a new kind of speculative invention, which though apparently trifling, and almost laughable, is nevertheless of great utility in assisting the genius to find variety for composition. By looking attentively at old and smeared walls (…) you may fancy that you see in them several compositions, landscapes, battles, figures in quick motion, strange countenances, and dresses, with an infinity of other objects. By these confused lines the inventive genius is excited to new exertions (…) It may be compared to the sound of bells, which may seem to say whatever we choose to imagine.”

In order to grasp the significance of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin’s reflection in the Virgin’s eye, to better comprehend the perceptual osmosis between the theological and the aesthetical, it is necessary to suspend judgement, for Leonardo reminds us that: “By these confused lines the inventive genius is excited to new exertions”. Our Lady of Guadalupe—the first of the twelve visions officially validated by the Church—is, according to improbable photochemical analysis, the only divine manifestation which combines in a double apparition the gaze and its image, the seer and his vision, the watcher and the watched. What occurred on Mount Tepeyac was similar to a… reciprocal apparition. The religious illumination and the Christian love of the believer for Mary recall another sentimental, Flaubertian education, that of Frédéric for Marie Arnoux.

What he then saw was like a vision.

She was (…) all alone, or, at least it appeared so to him; he could see no one else, dazzled as he was by her eyes. At the moment when he was passing, she raised her head; his shoulders bent involuntarily; and, when he had seated himself, some little distance away, on the same side, he glanced toward her.

The Virgin appeared to the Aztec and the Aztec to the Virgin. The Madonna appeared in the eyes of Juan Diego and Juan Diego appeared in the eye of the Madonna. Veni, Vidi me Virgine. The Virgin appeared to me. I appeared to the Virgin. Sono apparso alla Madonna, wrote Carmelo Bene. The reciprocity between Juan, “the eye which sees”, and Mary, “the perceived vision”, reveals the circular nature of gazing. The presence of the Virgin’s image on the believer’s coat corresponds to the reflection of “the bearded man” on the surface of the Madonna’s eye. It is also to be noted that the perceptual reciprocity between the watcher and the watched is at the origin of cinematography. The cinematograph of the Lumière brothers was initially designed to serve both as a film camera and as a film projector, which could capture light and project pictures at the same time. The presence of the watcher in the eyes of the watched also recalls another obsessional motif and pictorial fantasy: the real or imaginary presence of the painter in his own painting.

1434: The Arnolfini Portrait, oil on oak by the Flemish artist Jan Van Eyck. The name of the artist and the date of composition are not to be found on the surface of the painting, but inside the painting itself, at the far end of a bedroom where a husband and his wife are portrayed full-length. The signature is at the far end, on the wall situated behind the couple: Johannes de Eyck fuit hic 1434 (Jan van Eyck was here, 1434). Below this inscription, we can see the famous convex, spherical mirror, whose frame is decorated with ten medallions in byzantine style relating the Passion of Christ. On the surface of the mirror, the husband and his wife are reflected from behind and, facing them, at the other end of the room, the figures of one or more persons framed in the doorway. Who are they? The artist painting husband and wife? Or the legal witnesses of the couple? Pictorially speaking, the viewer could be situated between the couple and the witnesses. But physically, he is nowhere. And naturally, the mirror in the painting does not reflect the image of the viewer inside the painting. For man cannot be reflected in a painting, no more than a vampire can in a mirror. In his book Secret knowledge, Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, David Hockney explores the role played by the camera oscura in the creation not only of geometrical perspective but also of the fabrication of visual effects and the manipulation of perception. Beyond a mere mise en abyme, thanks to the hyper-realistic effect of the mirror, Van Eyck substitutes a more imprecise notion, that of the illusion of the mind, for the classical notion of optical illusion.

“The Arnolfini Portrait” (1434) - Jan Van Eyck -

Oil on oak - 82 x 60 cm (The National Gallery, London)

“The Arnolfini Portrait”, detail

One century later, in 1531, the watcher can finally project himself inside the picture, thanks to a miraculous camera oscura. In the same way as Van Eyck, we could say: Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin fuit hic, 1531. As the English proverb and the French prophet Marcel Duchamp put it: “Beauty lies in the eye of the beholder — It is the watcher who makes the artwork.” Juan Diego, witness and receptacle of the apparition is, in spite of himself, the author of the vision printed on his coat. A contemporary of Michelangelo (1475-1564), Juan Diego (1474-1548) could somehow be the discoverer or the inventor of the Virgin of Guadalupe; “inventor”, not in the sense of a hoax, but in the legal, juridical and archaeological sense of the term. Thus the person who discovers a prehistoric cave and who is the first to set eyes on a rupestrian painting which has remained hidden, secret and invisible in the dark for millennia, is called an “inventor”. The most incredulous of people, the beloved children of the critical mind, will retort that the representation of the Virgin of Guadalupe is neither a corporeal imprint nor a photographic image, but a pictorial representation. Could the revealed apparition of the Virgin be first and foremost a metaphor of representation? Therefore the negation of the miracle and all radical incredulity—reinforced by numerous hoaxes— do not make much sense, for the religious apparition is an imaginal reality which is fundamentally poetic, or acheiropoetic. While visiting the Bill Viola retrospective in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1998, Peter Sellars asked the visual artist: “Once the museum is closed, the lights switched off, the machines unplugged, the film projectors and the TV screens turned off, do the video installation still continue to exist?” We could pursue this questioning further: “If a tree falls in a forest and there's no one there to hear it, does it make a sound?” or “If Mary appears on top of Mount Tepeyac and there's no one there to see her, is she visible?” There is no doubt that the tree will fall, but Mary could not appear if no one was around to witness the apparition.

The nature of a Marian apparition is to appear before the eyes of a watcher. Is an apparition possible without a watcher? If Actaeon had not accidentally seen Diana in the woods, surrounded by nymphs, bathing her virginal naked body in limpid waters, would it mean that the event—although fictitious or mythological— could not have occurred? If Diana had not seen him, he would not have been changed into a stag. But if Actaeon had not witnessed the scene, Diana would still have bathed. On the contrary, the apparition of the Virgin is a visual phenomenon which has no reality in itself, outside the person who witnesses it. Although transcendental, the divine apparition is not something per se, objective and independent from any possible experience. What Juan has subjectively seen is not a noumenon but a thing for itself, a phenomenon.

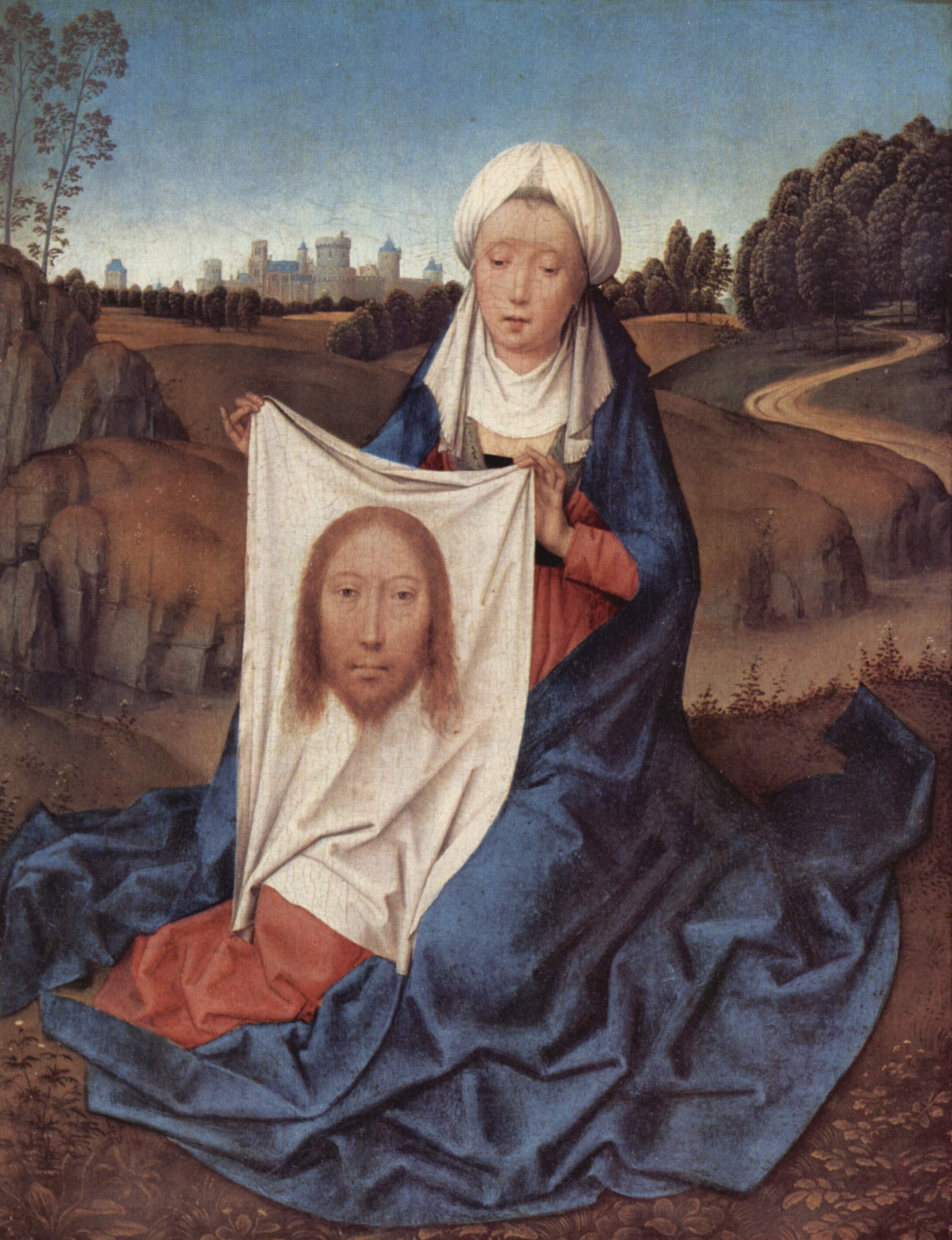

The representation cannot be without appearing. Its essence is to appear. Saint Veronica uses her veil to wipe the sweat from Chris’s face. Once dried, the sweat becomes a shroud. The image of Christ’s face appears on the veil covered with salt crystals like photographic paper coated with silver grains. Veronica’s veil is a popular Christian legend with a strong iconographic power. This tautologically pictorial motif, this representation of the representation (itself a re-presentation) is the equivalent of a statement of faith for a painter. Memling in Flanders, Pontormo in Florence and El Greco in Toledo have painted this scene. This allegory of representation can be compared to the folk etymology of the name Veronica, being the contraction of truth and image: vera and icon.

“Saint Veronica" (obverse) (1470) - Hans Memling -

Oil on panel 32 x 24cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

“Veronica and the image” (1515) - Pontormo - fresco

(Santa Maria Novella, Florence)

"Veronica with the Holy Face" (1579) - El Greco -

Oil on canvas - 71 x 54cm (Santa Cruz Museum, Toledo)

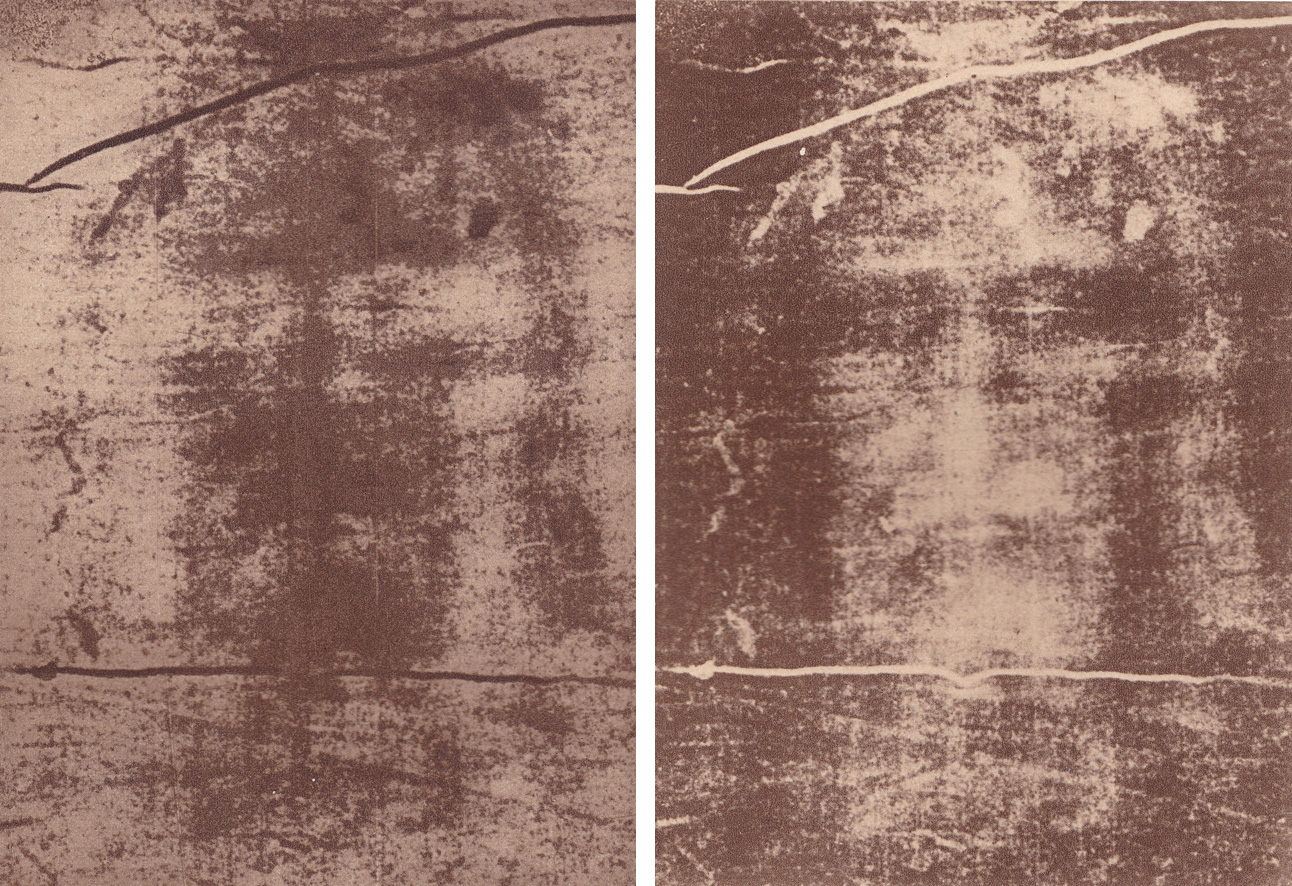

The Shroud of Turin perpetuates the photographic metaphor. Following its appearance as early as the 14th century, the Holy Shroud has continually been revered since then. But it was necessary to wait for the birth of photography before the miraculous dimension of the imprint of Christ’s face could be allowed to express itself fully. On May 28, 1898, in a chapel of Turin Cathedral, the amateur photographer Secondo Pia, like Neil Armstrong in the Sea of Tranquility, made “one small step for man, one giant leap for Christendom”. At 9:30 PM, in the darkness of the church, the photographer immortalized the face of the eternal with an artificial light. Strictly speaking, it is one of the first studio photographs ever, since it was made with the aid of electrical lighting. Midnight struck. It was time to develop the photographic plates. The unthinkable was about to be revealed. An Italian coincidence: Secondo Pia is fortunate and aptly named. His name is the reverse image of Pio Secondo, Pius II in English, 210th pope since the apostle, the first bishop of Rome, Saint Peter. The photographic revelation is commented by Paul Claudel, who writes that it is “so important that I can only compare it to a second resurrection (…) And now, after so many centuries, the obliterated image suddenly reappears on the Shroud’s fabric with a dreadful truthfulness, with the authenticity not only of an irrefutable document, but of a present fact. The interval of nineteen centuries is suddenly erased; the past is transferred to the present. (…) More than an image, it is a presence. More than a presence, it is a photograph, something printed and indelible. More than a photograph, it’s a negative, that is a hidden activity (a little like the Holy Scriptures themselves, if I may be so bold to suggest) and capable under the lens to achieve an evidence in positive. Suddenly, in 1898, (…) we are in possession of the photograph of Jesus. Just like that!”

Just like that, on the negative of the photographic plate, Secondo Pia, astounded, discovered the positive image of Christ, which had remained invisible to men’s eyes and was finally revealed by the grace of the photons and their graphy. As if to better contradict Walter Benjamin’s thesis, the technical reproducibility of photography, far from leading to a loss of aura, conveys a new and sacred splendor to the object.

“Positive and negative photographs of the Shroud of Turin” (1898)

Secondo Pia

In the speech delivered in Turin in May 2010 during a pastoral visit, Pope Benedict XVI offered a meditation on the Veneration of the Holy Shroud. According to the Bavarian-Roman Pope, the image could not have been painted with pigments: “The Holy Shroud is an Icon written in blood. One could say that the Shroud is the Icon of this mystery, the Icon of Holy Saturday. (…) Yet the death of the Son of God, Jesus of Nazareth, has an opposite aspect, totally positive, a source of comfort and hope. And this reminds me of the fact that the Holy Shroud acts as a "photographic' document, with both a "positive" and a "negative". And, in fact, this is really how it is: the darkest mystery of faith is at the same time the most luminous sign of a never-ending hope.” The Holy Shroud is a metaphor incarnate which unites opposite realities. The most obscure is at the same time the most invisible and the most luminous. In the hour of solitude, contemplation dawns and on this Holy Saturday “the earth is shrouded in deep silence” and “What we take, in the presence of the beloved one, is merely a negative film; we develop it later, when we are at home, and have once again found at our disposal that inner darkroom, the entrance to which is “barred” to us so long as we are with other people.”, writes Marcel Proust in the shadow of young girls in flower. Beneath the heap of roses lays the image of the beloved one or of the Virgin Mary.

On December 12, 1531, the apparition of the Mexican Virgin—whose iconographic power was extraordinary—occurred a few years before the “Decree on the Invocation, Veneration, and relics of Saints, and on Sacred Images”, December 3, 1563. Written during the 25th session of the Council of Trent, the text is considered as a founding political act of the birth of the Baroque. The Roman Catholic Church decided to fight the Lutheran revolution not only with weapons and words, but also with images. The Church chose to “spectacularise” the Word of God. “Moreover, that the images of Christ, of the Virgin Mother of God and of the other saints, are to be had and retained particularly in temples, and that due honor and veneration are to be given them. Not that any divinity, or virtue, is believed to be in them, on account of which they are to be worshipped, or that anything is to be asked of them, or that trust is to be reposed in images, as was of old done by the pagans who placed their hope in idols (Ps 135, 15-17); but because the honor which is shown them is referred to the models which those images represent. In such a way that by the images which we kiss, and before which we uncover the head and prostrate ourselves, we adore Christ and we venerate the saints, whose similitude they bear: as, by the decrees of Councils, and especially of the second Synod of Nicaea, has been defined against the opponents of images.”

Long before the Manifestos of the Communist Party (1848), Dadaism (1916) or Surrealism (1924), the Vatican text can be considered as the first manifesto of the politico-aesthetical history of “modern” art. By modern, we mean the modern era which began with the conquest of the Americas, among them the Aztec Empire to which Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin belonged. Thus is reformulated a new critical doctrine of images, which takes into account the crime of iconolatry. The Church decides to promote images and their usefulness to teach and convert while removing any suspicion of idolatry. The idols are not only pagan. They are also ghosts, empty shells in which superstitions can hide. The mention of Psalm 135, 15-17 in the decree of the Council refers to the “acheiropoeitical” origins of the transcendental image, those miraculous images made without hands, such as the linen imprint of the pictorial image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

The idols of the nations are silver and gold,

the work of human hands!

They have mouths, but do not speak;

they have eyes, but do not see;

they have ears, but do not hear,

nor is there any breath in their mouths.

If the pagan idols are the work of human hands (with an exclamation mark), the Christian idols are undoubtedly of another nature. “The honor which is shown them is referred to the models which those images represent.” The question of the model is posed. The painter and art critic Giorgio Vasari will answer it in his own way in one of his last works: the fresco of Saint Luke painting the Virgin (1565). We discover the Virgin and child posing as a model, standing in a cloud of ether and cherubs. Sitting on a stone stool, Saint Luke is painting the scene. We see double: both the “actual” Virgin and the one in the painting. Saint Luke’s work, on an easel, shows a Virgin and child painted on wood, seen in a three-quarter profile and in a low-angle shot, while the viewer sees the other Madonna in profile—Vasari’s Virgin on fresco. The almost frontal perspective of the clouds which reinforces the bi-dimensional aspect of the scene conveys the impression of watching an image floating in the air, an apparition. Is Saint Luke painting the Virgin or an apparition of the Virgin? Under the cloud of the Madonna, there is a phial, an open rectangular wooden box containing brushes, against which leans the painter’s palette. The mannerist and cloudy apparition seems to have popped out of this paint box as if a jinni out of a wonderful lamp. Like in the anonymous work from the 18th century mentioned above, God painting the Virgin of Guadalupe, in Vasari’s Saint Luke painting the Virgin, we can see the saintly painter holding a brush in his right hand and balancing a palette in his left with his thumb in the hole. Therefore, there are two palettes in the fresco, in the same way there are two painters in the scene, one visible, inside the image—Saint Luke—and another invisible, the demiurge who is absent from the fictitious representation—Vasari. The ox is present, lying down behind Saint Luke, like in a painting depicting the birth of Christ. The Nativity animal reinforces the allegorical dimension of the work. Which allegory, exactly? The religious allegory is eclipsed by a pictorial allegory, an allegory of artifice which refers “to the models which those images represent.”

“St Luke painting the Virgin” - Giorgio Vasari (1565) - fresco

detail

“St Luke painting the Virgin” - Giorgio Vasari (1565) - fresco

(Basilica della Santissima Annunziata, Florence)

Once his mission is accomplished in Holyhood, the agent Jesus Maria Veronica is recalled to the Vatican. Etymologically, Vatican is based on Vaticinium, Vates or Vatis, which may refer to divination and belief. The Vatican is the source of extraordinary witticism. In French: “Eh bien ! moi je te dis : Tu es Pierre, et sur cette pierre, je bâtirai mon Église,” (“And I say also unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church,” St Matthew, 16-18— the name “Pierre” for “Peter” and the French word for “rock” or “stone”, “pierre”, being identical). In English, the French “Saint Siège” is the “Holy See”; yet the connection between the “eye” and the notion of holiness is fortuitous. Once again, it is necessary to have words say the contrary of what they think. “Pierre and “pierre” are identical in French only. Santa Pietra in Italian or Saint Stone in English are mere figments of our imagination. The term “see” is derived from the Latin word “sedes”, “seat” in English: the episcopal throne.

“Saint Veronica” (1630) - Francesco Mochi

(St Peter’s Basilica, Rome)

In Saint Peter's Basilica, there is a sculpture of the True Holy Image, the Vera Icon: Saint Veronica. In this Baroque work by Francesco Mochi (1630), the face of Christ is chiseled into the creased marble veil. The image and the flesh, the cloth and its rippling, have been turned into stone, as if under the gaze of Medusa. The folds and creases of matter are to art history what the sense of grotesque and sublime simulacre is to Baroque fiction. It reminds us that, in the fashion of Shakespeare and Calderón, all the world’s a stage and life is a dream.

All the world's a stage

La vida es sueño

Stare at the four black dots in the center of the image for approximately 15 seconds. Then close your eyes and, without opening them, look up. Then behind your darkened eyelids…

Alessandro Mercuri

(translated from The French by Blandine Longre and Paul Stubbs)

TAGS : The adventures of Jesús Maria Veronica, Holyhood, Michelangelo, Mexico, Mount Tepeyac, Virgin Mary, Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, Juan de Zumárraga, Milky Way, Luis Buñuel, Marian apparition, miracle, Pope John Paul II, Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, acheiropoieton image, God painting the Virgin of Guadalupe, icon, camera oscura, representation, Madonna, Shroud of Turin, Saint Veronica, Alfonso Marcue, illumination, pareidolia, Leonardo de Vinci, Gustave Flaubert, Carmelo Bene, The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan Van Eyck, David Hockney, optical illusion, Bill Viola, Peter Sellars, Memling, Pontormo, El Greco, Secondo Pia, Paul Claudel, Pope Benedict XVI, Marcel Proust, Council of Trent, Baroque, iconolatry, Giorgio Vasari, St Luke painting the Virgin, Vatican, Francesco Mochi, Shakespeare, Calderón, Bruno Latour

NEXT POST >>