SNOOPY

SNOOPYRebel With a Cause

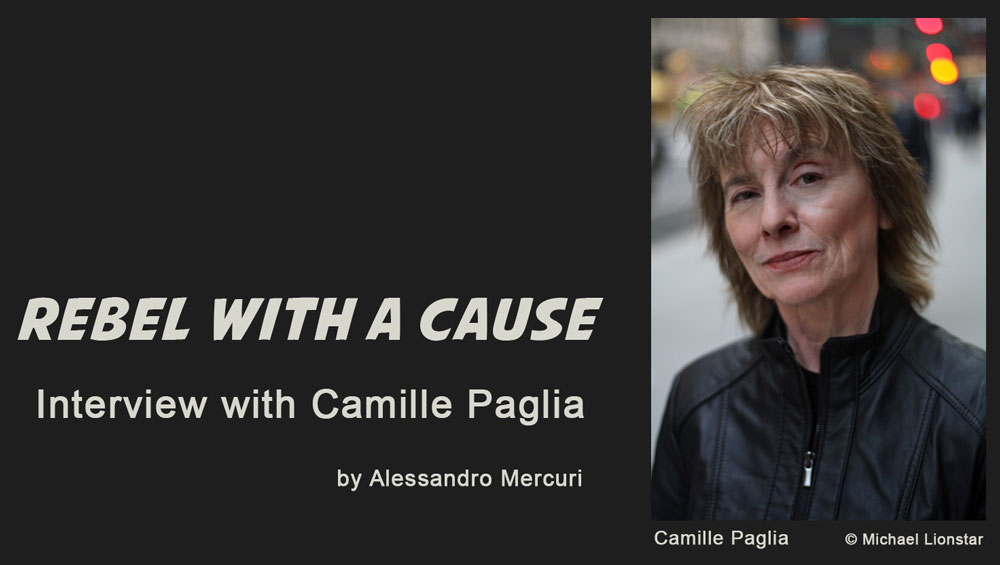

Camille Paglia __ February 18, 2013

On the release of her new book on art history entitled "Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars" (Random House, 2012), American author and social critic Camille Paglia has been interviewed by ParisLike about her intellectual journey, her views on free thought, activism and her critical approach to dogmatism.

Alessandro Mercuri: You often refer to your Italian heritage and to the pagan dimension of the Roman Catholic Church. From the Renaissance to the age of the Baroque, the representation shifted from iconic Christian art to the painting of Greek myths and metamorphosis. This artistic revolution, in which Jesus and Dionysus coexist or like Bernini's Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, seems important to your vision. It's almost as if postmodern visual issues dated back from the Renaissance. How do you relate this artistic period to your interest in our modern mass media culture?

Camille Paglia: The principal over-arching idea of my work is that Western culture has been formed by a long, irresolvable conflict between ancient paganism and Judeo-Christianity. I state in my first book, Sexual Personae, that it is a historical error to claim that Christianity defeated paganism at the start of the Middle Ages. No, paganism went underground and erupted, in my view, at three key moments: the Renaissance (a revival of Greco-Roman humanism and aesthetics); Romanticism (a return of Dionysian nature-worship with its emotionalism and its primal sexuality verging on the barbaric); and modern popular culture (Hollywood as a restoration of the pagan pantheon of physically perfect, openly sexual gods and goddesses).

The Triumph of Bacchus by Diego Vélasquez (1629)

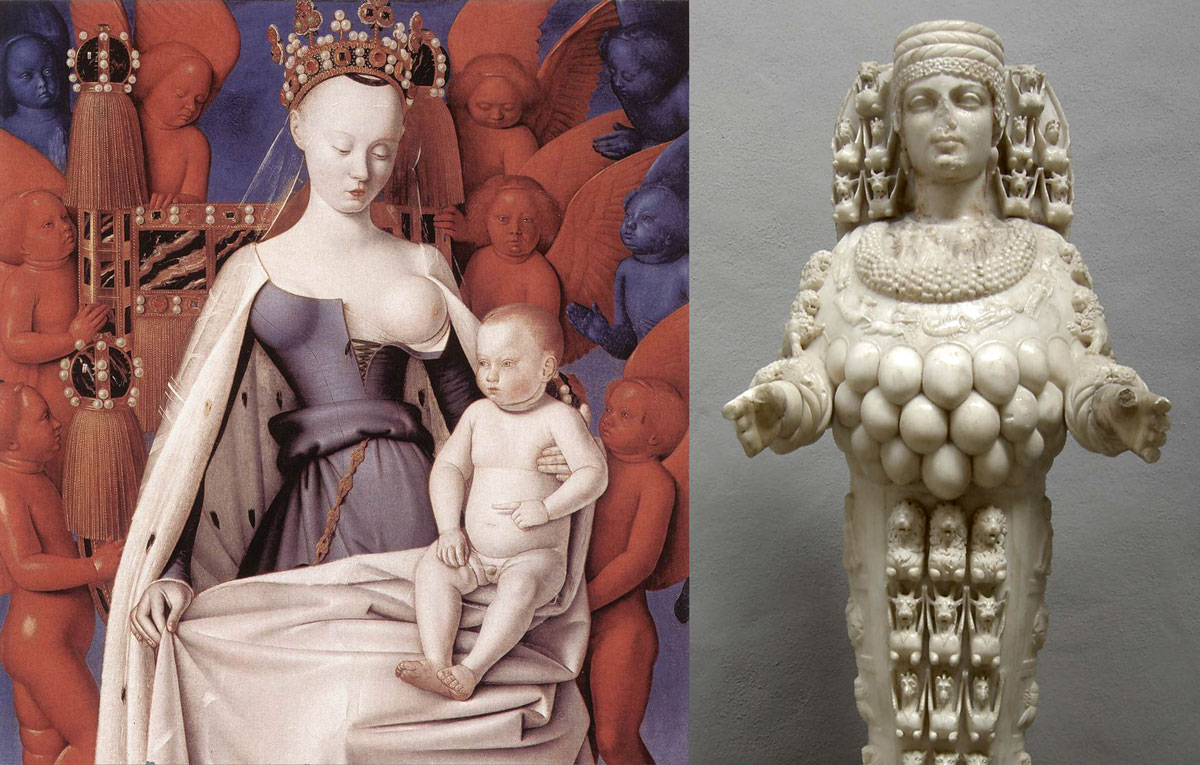

Paganism was stubbornly preserved among the rural Italians who were my ancestors. (My mother was born in Ceccano in Lazio, and my paternal grandparents were born in the Campania around Avellino and Benevento.) Indeed, the Latin word “paganus” meant “person of the countryside”—initially untouched by the trend of Christianity that arrived from the Eastern Mediterranean and first took root among the patricians in Rome. The worship of the great goddesses of antiquity (Cybele, Isis) eventually took new form in the cult of Mary, which the Protestant reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin correctly attacked as an intrusion into biblical Christianity. Similarly, veneration of the saints (also rejected by Protestants) was a survival of paganism. In some cases, gods were simply re-named, as happened when the Roman god Janus became Saint Gennaro, the patron of a huge annual festival in New York’s Little Italy.

Melun Diptych / Virgin and child by Jean Fouquet (1452-1458)

Cybele / Artemis of Ephesus - Roman copy - 1st century CE

For me, the creation of “glamour” by the Hollywood studio system in the 1930s (notably by M-G-M and Paramount) had magical pagan properties. I am still obsessed with the movies made during that great period, when ordinary men and women were turned into divinities by the vast machinery of the star system. The glamour portraits by photographers George Hurrell or Edward Steichen, who show Hollywood stars radiating with dazzling charisma, are as beautiful to me as great masterwork paintings. Today, Hollywood stars are ordinary and banal—too familiar to us because of the excess number of award shows and casual photos snapped by paparazzi in the street. The movies, as well as their stars, have lost their magic.

Jane Russell by George Hurrell, 1941

A.M.: Your work could be considered in connection with the idea of freethinking outside the ideologically legitimate paths or ideologies whether dogmatically feminist or Marxist. Thinking beyond good and evil in a Nietzschean way seems to be for you an essential moral attitude. As a social activist who grew up in the sixties, you've been fighting against many forms of power including political correctness. What is the function of an intellectual or thinker in today's American or global society?

C.P.: I left the Roman Catholic Church when I discovered that it would not tolerate free thought and free speech. The moment was very precise: I was sitting in a church pew as a nun was instructing us in the “Religious Education” class for which Catholic students were released one afternoon per week from public high school in Syracuse, New York. At one point I asked, “If God is all-forgiving, is it possible he will ever forgive Satan?” The nun’s reaction to what seemed to me (then and now) as a very interesting question was astounding. She turned red and began shouting angrily at me in a way that I found both rude and irrational. That was the end of my attempts to initiate any kind of dialogue with the Catholic hierarchy.

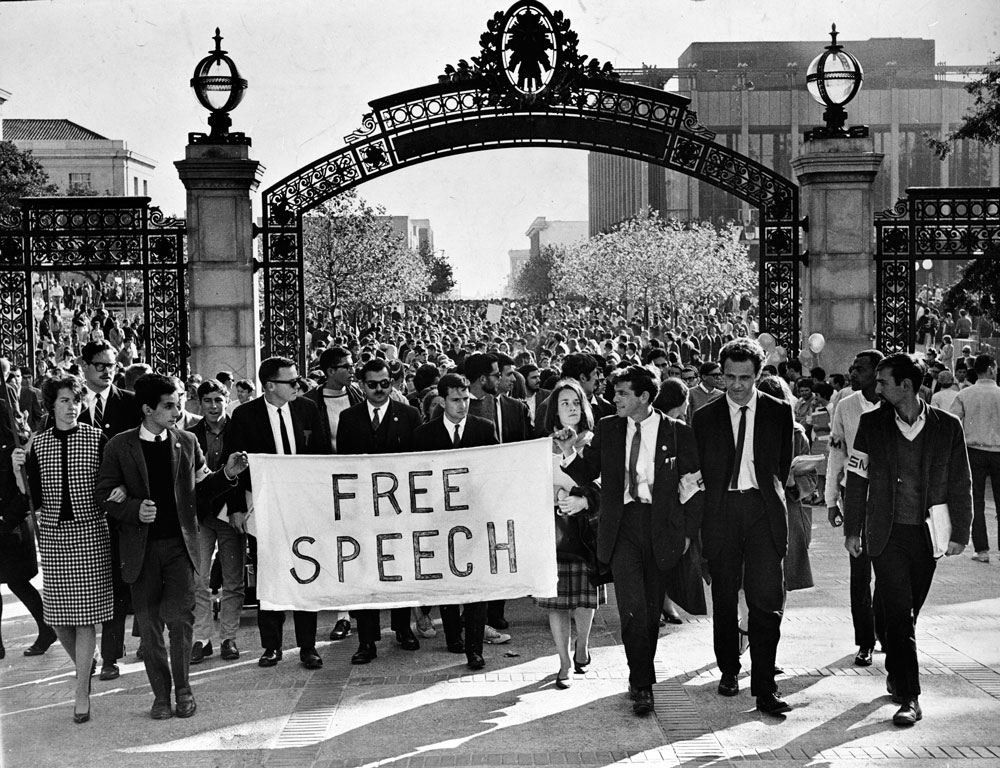

My commitment to free thought and free speech is a primary, foundational principle of my life and career. The radical Free Speech movement at the University of California at Berkeley exploded into the news during the same month (September 1964) that I entered college. It was for me the essence of the fiery and rebellious 1960s spirit. Hence I do not understand the disastrous descent of my generation into the era of political correctness which began in the 1970s. Both liberalism and feminism became outrageous suppressors of free speech—all in the name of an ideological purity that soon resembled the authoritarianism of the Roman Catholic Church. Liberal “speech codes” are now deeply established at all major colleges and universities in the U.S. There are severe penalties for “offensive speech”—usually something which wounds the feelings of a particular protected group (women, blacks, gays, etc.). The situation is absolutely outrageous. It is partly why cultural criticism in the U.S. has become so insipid and mediocre. Students are trained to obey, not to think.

Free Speech Movement lead by Mario Savio at UC Berkeley

picture by Chris Kjobech - nov. 20, 1964

There are no intellectuals left in the U.S. Several years ago, Bernard-Henri Lévy said after visiting the U.S. and lecturing at major universities, including Harvard, that he had met no intellectuals in America—only partisans. He was exactly correct! The leading humanities professors at the elite colleges and universities strike poses of fashionable Leftism, but they are naïve about economics and history, and they simply parrot the latest shallow “talking points” of the Democratic Party. I am a registered Democrat (I voted for Obama in 2008 but the Green Party in 2012, as a protest against the Obama administration’s military adventurism), but I consider it the obligation of an intellectual to critique all political positions and parties, including his or her own. The herd-like groupthink of American liberals is childish and cowardly. It is just as intellectually inert as the antiquated religious dogma on the conservative Right.

The polarity of Left versus Right is not a universal aspect of history. It dates only from the late eighteenth century. How absurd to treat these increasingly clichéd concepts as eternal absolutes—just as medieval theologians regarded divine law. It is the duty and function of the intellectual today to remain outside of all categories and to attack cliché and cant wherever they appear.

A.M.: In the 2006 Drexel InterView you mentioned that you and Andy Warhol grew up in an industrial town, Endicott NY for you and Pittsburgh for Warhol. As the pope of pop art, you've been witnessing the tremendous impact of popular culture and mass consumerism. Like him, your views are not fueled with a critical so-called armchair leftist approach. As you put it, you "don't want to ignore the commercial mission of popular culture or its financial underpinning" but you also say that: "I'm an appreciator, an enthusiast. I'm a fan, I celebrate." Could you tell us more about this concept of celebration?

C.P.: I detest the cynicism of post-structuralism and postmodernism, which pretend to discover deception and slippage in every text, no matter how revered. This methodology has become a tiresome gimmick—snide game-playing of the kind that infatuates callow adolescents. The once daring and authentically avant-garde gestures of Marcel Duchamp or Salvador Dalí have become the pretentious stock-in-trade of third-rate academics. I am a fierce and savage critic known for my attacks on false ideas or inflated reputations, but my most characteristic mode is celebration—whether of the Nefertiti bust or early Madonna videos. It is important to honor art in all its forms and to communicate that enthusiasm to students. But the elite universities today are filled with careerist vandals who systematically destroy their students’ ability to appreciate and value art.

True Blue - Madonna - music video by James Foley (1986)

As for commercialism, I am well-positioned to reject the rote condemnation of capitalism that flows from humanities professors ignorant of economics. As the product of an Italian immigrant family, I personally witnessed the transition from a static, tribal, agrarian culture in the old country to industrialization in an American factory town to today’s middle-class, office-centered professional life. It was capitalism that gave opportunity and liberation to my family, which escaped the impoverished Italian countryside. My entire life as a teacher and writer was made possible by capitalism. Indeed, capitalism gave birth to the modern emancipated woman, who for the first time in history is no longer dependent on a father or husband.

A.M.: You're known as an intellectual figure and essayist. What seems most relevant for you in the phrase "non narrative writer" is ostensibly the word "writer". You said once that most people don't write sentences anymore and that for you writing is architectural. Your preference is more for the aphorism or the epigram than to long, abstract and laborious developments. The intimate "I" who also guides your writing is not an abstract and disembodied objective narrator. Your work is filled with passion, a certain form of creative paranoia or a kind of rebellious "hubris". What is your viewpoint on the essay as a literary genre in the history of literature?

C.P.: It is certainly true that I love the epigram, which I first studied in a British book that I stumbled upon in a second-hand bookstore during high school: The Epigrams of Oscar Wilde. It was a collection of short, startling quotes from Wilde’s essays, plays, and conversation. Wilde’s imperious tone was partly derived from Baudelaire, an uncompromising apostle of art and beauty who would later deeply influence my work. I also read about the 1920s Algonquin wit Dorothy Parker and her talent for devastating barbs. In fact, I was inspired by an amusing cartoon drawing of Parker wearing a dress but holding a dripping pen like a spear that she was about to fling, as if in battle. That is exactly how I think of my writing! My long appreciation of the epigram form helped me enormously when I was suddenly the subject of media attention in 1990, after the publication of my highly controversial first book. Newspapers and magazines found that I was very “quotable”. They could ask me about anything, and I would instantly produce vivid “one-liners” that fit perfectly in their news stories with limited space. It’s simply the way I think and talk! Through so many years of practice, I have the ability to project my personality and polemical positions into a single sentence. I remember being intrigued in college by fragments of Greek lyric poetry: sometimes only a single line survives from the work of many famous poets, including Sappho, and yet that one line contains everything. I admire that quality of concise intensity and try to imitate it.

As for long developments of thought, Sexual Personae itself, a 700-page magnum opus which took 20 years to write, is one of the most ambitious and complicated works of non-fiction ever produced by a woman. Its ancestry is in Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, an immense and imposing work that I first read and admired when I was 16. I would point to my chapter on Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest as an example of innovative argumentation. It is implacable in its series of surprising turns and ascents. The structure of that long chapter is completely original and without precedent in literary criticism.

A.M.: In terms of French intellectual influences, you often mention your admiration for Sade and his philosophy of nature and you aversion for the French theory and thinkers such as Foucault and Derrida. How could you define the creative influence of the former and the negative influence of the latter?

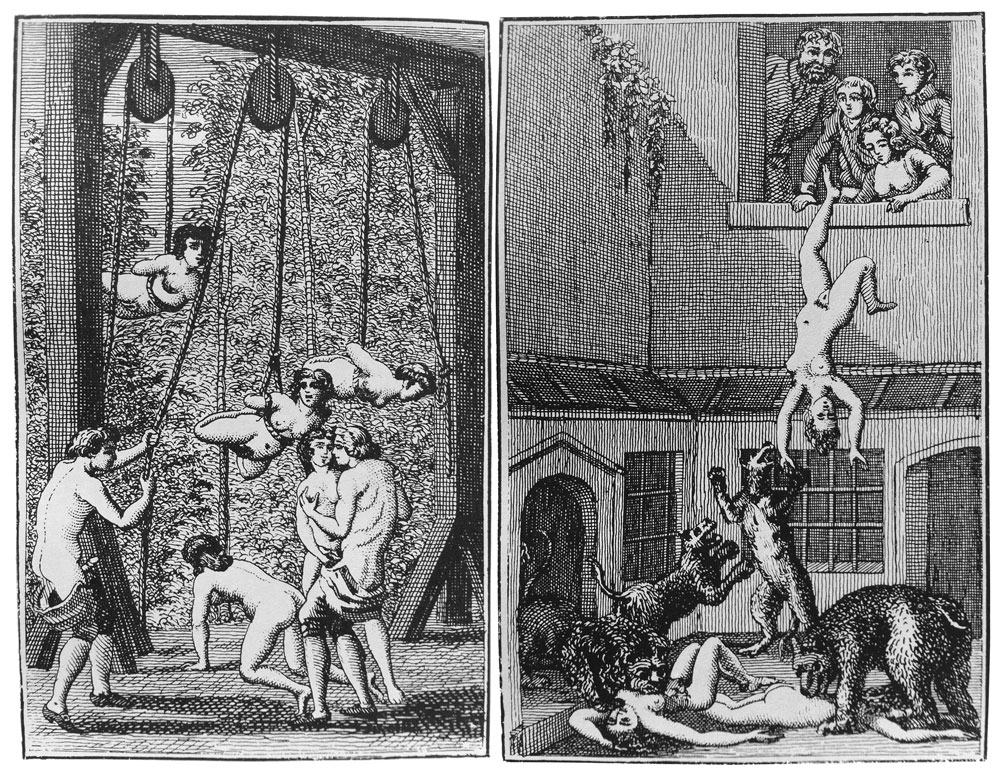

C.P.: Sade was a figure of towering imagination and incessant creativity. He penetrated to the heart of the West’s moral systems; he exposed every taboo in order to violate it. What a mind! He was also a scathing satirist who could generate comedy out of horror. Sade’s major works were available everywhere in Grove Press paperbacks when I was in college and graduate school. He was hailed as a prophet of the sexual revolution. Then he disappeared from U.S. bookstores. Humanities academics shamefully stampeded after Derrida, Lacan, and Foucault in the 1970s. Sade was erased and forgotten. It is an unforgivable scandal. Post-structuralism may have been needed in France, with its heavy burden of great high culture along with its Racinian constraints on language, but it was completely unnecessary in the U.S., where there has never been an oppressive high-culture establishment. Quite the opposite! America is the land of Hollywood, hamburgers, and fast cars. Derrida, Lacan, and Foucault had nothing to contribute to American criticism, which should have gone in the direction of Marshall McLuhan and Leslie Fiedler instead (two pivotal influences on me in college).

Engravings from Juliette by the Marquis de Sade (1801)

Beyond that, Foucault is a fraud. In 1991, I wrote a long and detailed attack on post-structuralism, centered on Foucault: “Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders: Academe in the Hour of the Wolf” (it was reprinted in my first essay collection, Sex, Art, and American Culture). Every important new idea which misinformed acolytes attribute to Foucault was deviously borrowed by him from someone else—from Émile Durkheim to Erving Goffman. Foucault was completely unscholarly. He knew very little about any subject, including classical antiquity and sexuality, and he did not bother to do deep research. A century from now, the naive fad for Foucault will look as bizarre as the feverish fad for Emanuel Swedenborg looks to us now. Too many secular humanists, having abandoned religion, are still looking for a Messiah or father figure. As I once wrote, “Better Jehovah than Foucault”—because at least Judeo-Christianity has a great book of visionary Hebrew poetry to offer.

A.M.: In France, the current socialist Minister of Women's Rights, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem wants to abolish prostitution and to eradicate it from society. Most French feminists have praised the project while many prostitutes have expressed their disapproval. What is your view and your libertarian approach on such an issue?

C.P.: French feminists want to abolish prostitution? What reactionary Puritanism. What has happened to the France of the great art films which electrified me in college because of their daring sexuality and their seductive stars like the world-weary Jeanne Moreau and the young Catherine Deneuve? My position as a libertarian is that the state has no right to intervene in any matter involving our personal choice about our bodies. Hence prostitution, abortion, drug-taking, and suicide lie beyond the legitimate reach of the government. But while I would warn my students about the dangers of drugs (which produce short-term pleasure but long-term harm), I would express no such caution about prostitution, as long as it is voluntary. I support both prostitutes and prostitution whole-heartedly. I condemn the relentless assault by social workers and psychologists on the characters of prostitutes, who are endlessly portrayed as victims or products of abusive backgrounds. Yes, this might be true in some or even many cases, but it is not the whole story. As I have written, the most successful prostitutes are so intelligent and adept that they are invisible. It is perfectly reasonable to require that prostitutes not create a public disturbance; hence they should not loiter around schools or churches or aggressively solicit at sidewalk cafés. And it is also reasonable that brothels not be licensed in small apartment buildings where other residents might be inconvenienced. But in a modern democracy, prostitutes have a perfect right to conduct their lives as they wish. Whether they function as employees or independent operators, prostitutes provide an important service that has been of clear value to a significant portion of the population since civilization began. Indeed, their very existence, challenging the authority of Judeo-Christianity, is intrinsic to our freedom of sexual imagination.

Catherine Deneuve & Georges Marchal in Belle de Jour by Luis Buñuel (1967)

TAGS : Camille Paglia, Rebel With a Cause, Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars, Random House, social critic, Alessandro Mercuri, Italy, Roman Catholic Church, paganism, Judeo-Christianity, Sexual Personae, Dionysus, Hollywood, paganus, Cybele, Isis, Marie, San Gennaro, glamour, George Hurrell, Edward Steichen, political correctness, Satan, free thought, Free Speech, Berkeley, speech code, United States, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Democratic Party, Green Party, conservative Right, polarity of Left versus Right, Drexel InterView, Andy Warhol, post-structuralism, postmodernism, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dali, Nefertiti, Madonna, commercialism, capitalism, economics, The epigrams of Oscar Wilde, Baudelaire, Algonquin, Dorothy Parker, epigram, Greek lyric poetry, Sappho, Sexual Personae, The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir, The Importance of Being Earnest, Marquis de Sade, French Theory, Foucault, Derrida, university, academics, humanities, Lacan, Marshall Mc Luhan, Leslie Friedler, Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders: Academe in the Hour of the Wolf, Sex, Art and American Culture, Émile Durkheim, Erwin Goffman, Emanuel Swedenborg, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, prostitution, prostitute, French feminist, feminism, puritanism, Jeanne Moreau, Catherine Deneuve, libertarian