KISS ME DEADLY

KISS ME DEADLYReign in Blood

Erik Morse __ May 24, 2014

<> PDF

THE SECRET MARK THAT FRENCH PULP VILLAIN FANTÔMAS LEFT ON THE 20TH CENTURY

Fantômas II - Juve Against Fantômas (1913) - Louis Feuillade

In 1911 the bourgeoning ‘industry’ behind French cinema was controlled by two powerful surnames: Pathé and Gaumont. Since the first exhibition of the Lumière Brothers’ cinematograph in 1895, rival inventors, filmmakers and producers had vied for control of the public’s imagination with this wonderful new device. The first successful auteur was Georges Méliès, a magician, carnival performer and artist, who released a fantastic series of truc d'arrêt [“trick films”] between 1896 and 1905, including Voyage to the Moon and The Impossible Voyage through his own Star Films production company. Méliès’ oeuvre was a constant source of fascination for a public raised on the exotica of the fairground and the prestidigitation of the Robert-Houdin Theatre, stage for France’s most celebrated magicians. But Star Films was quickly overextended, and eventually outmatched by the appearance of a film factory system and the construction of suburban cinémathèques at the behest of rivals Pathé Frères and Leon Gaumont. Through the prolific direction of Ferdinand Zecca and Alice Guy, in-house auteurs for each company, Pathé and Gaumont were able to out-perform Méliès at his own game and monopolize cinema.

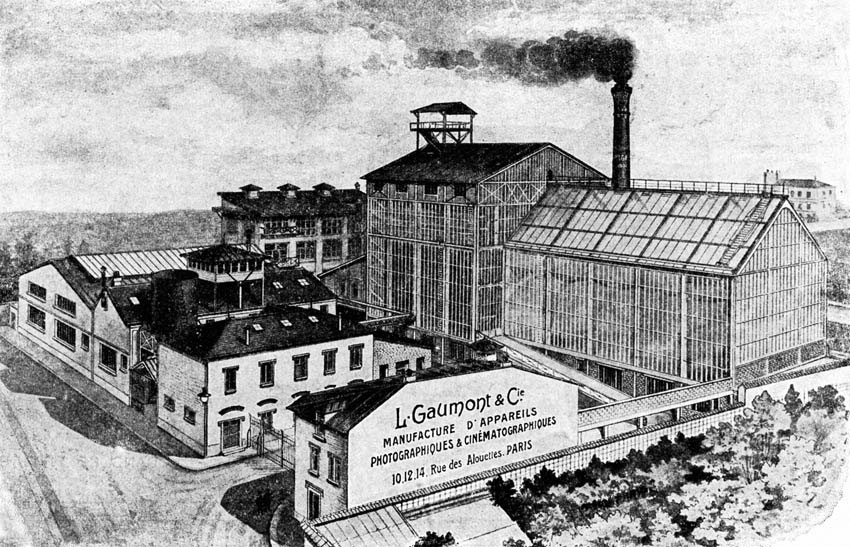

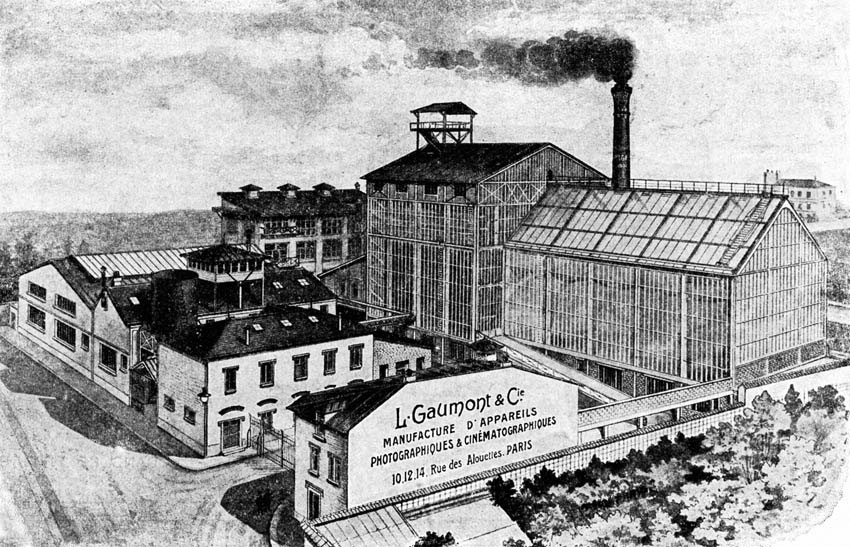

Louis Feuillade came to Paris from Lunel, Herault, in 1898, and following a brief flirtation with the right-wing press, entered the Gaumont system as a writer in 1905. His interests in literature and vaudeville made him an ideal candidate for creating and adapting short scenarios to capture the public’s imagination. He replaced Alice Guy as artistic director within two years and began a directing career that would span two decades and over 800 films. Feuillade’s earliest, inchoate shorts were heavily indebted to Ferdinand Zecca and Méliès, utilizing elements of fantasy, magic and trick photography. Nearly 200 films later, Feuillade would find his own unique cinematic eye. According to the Cinemathèque Française’s Jacques Champreux, “The series with the most ambitious realism to date, La Vie telle qu’elle est, completed in 1911, marked a watershed moment in Feuillade’s career…and the first symptoms of his genius which would burst open with Fantômas.” But as Fantômas was not the first crime serial of the new century, neither would it be the cinematic debut of the noir genre. Zecca had directed L’Histoire d’un Crime (which depicts a murderer’s journey to the guillotine) and Victimes de l’alcoolisme, while Victorin Jasset had filmed a successful series of villain-versus-detective serials, including Zigomar contre Nick Carter (which set Léon Sazie’s criminal against the famous American pulp detective). Feuillade and Leon Gaumont were eager to make their own crime film in hopes of competing with Pathé. After negotiating the film rights for Fantômas, Feuillade commenced production at the Cite Elgé studios at Buttes Chaumont in early 1913. There, amidst the daily pandemonium of the burgeoning dream factory, he would craft some the greatest of cinema’s earliest masterpieces.

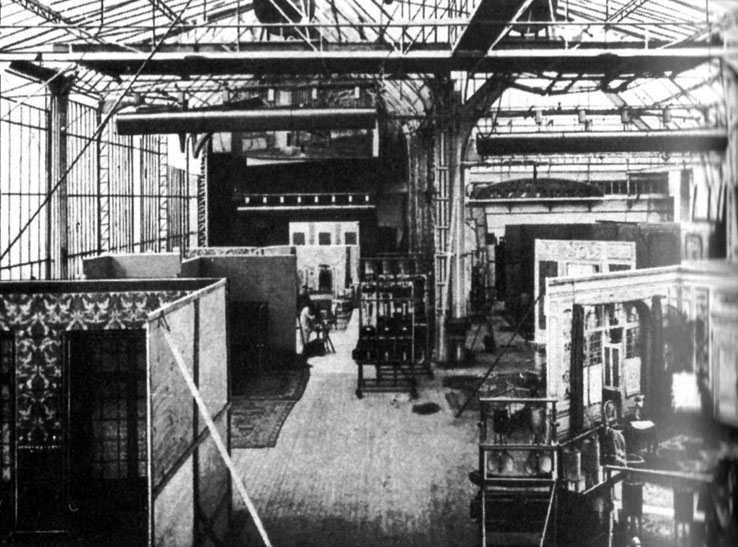

Buttes Chaumont Gaumont Studios

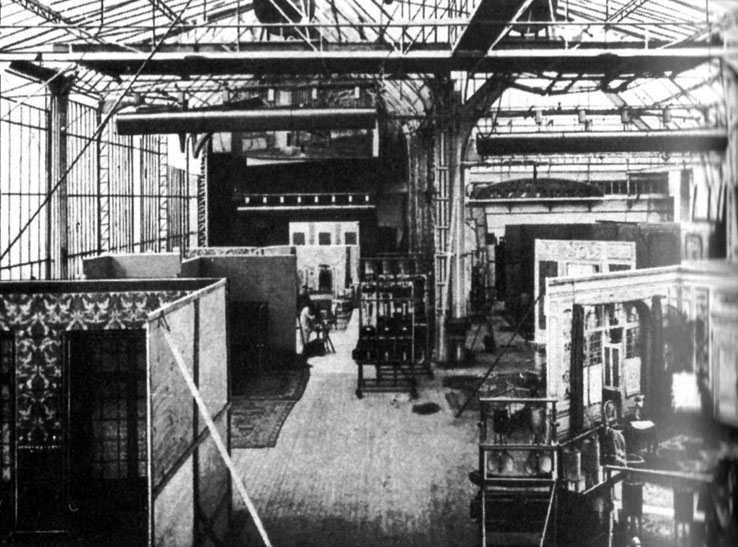

Glass-house studio at the Buttes Chaumont Gaumont Studios

“Although it is situated within Paris, on the side of the Chaumont hills, the factories of Gaumont have their own streets, trams, clothing stores, furniture depots, workshops for woodworking, of sculpture and painting, a printing works, a workshop for artists, théatres and…zoological gardens,” wrote a local reporter of the director’s workshop at the time. “Gaumont city is the city of the cinema.”

Feuillade’s technique was improvised play from the actors based on loose scenarios culled from the adapted volume. In What is Cinema?,Volume One, Cahiers du Cinema critic Andre Bazin explained Feuillade’s “writerly” technique as it proceeded throughout his directorial career:

Feuillade had no idea what would happen next, and filmed step-by-step as the morning's inspiration came…hence the unbearable tension set up by the next episode to follow and the anxious wait, not so much for the events to come but for the continuation of the telling, of the restarting of an interrupted act of creation…Both the author and the spectator were in the same situation, namely that of the King and Scheherazade; the repeated intervals of darkness in the cinema paralleled the separating off of the Thousand and One Nights. The “to be continued” of the true feuilleton [serial] as of the old serial films is not just a device extrinsic to the story. If Scheherazade had told everything at one sitting, the King, cruel as any film audience, would have had her executed at dawn. Both storyteller and film want to test the power of their magic by way of interruption to know the teasing sense of waiting for the continuation of a tale that is a substitute living which, in its turn, is but a but a break in the continuity of a dream.

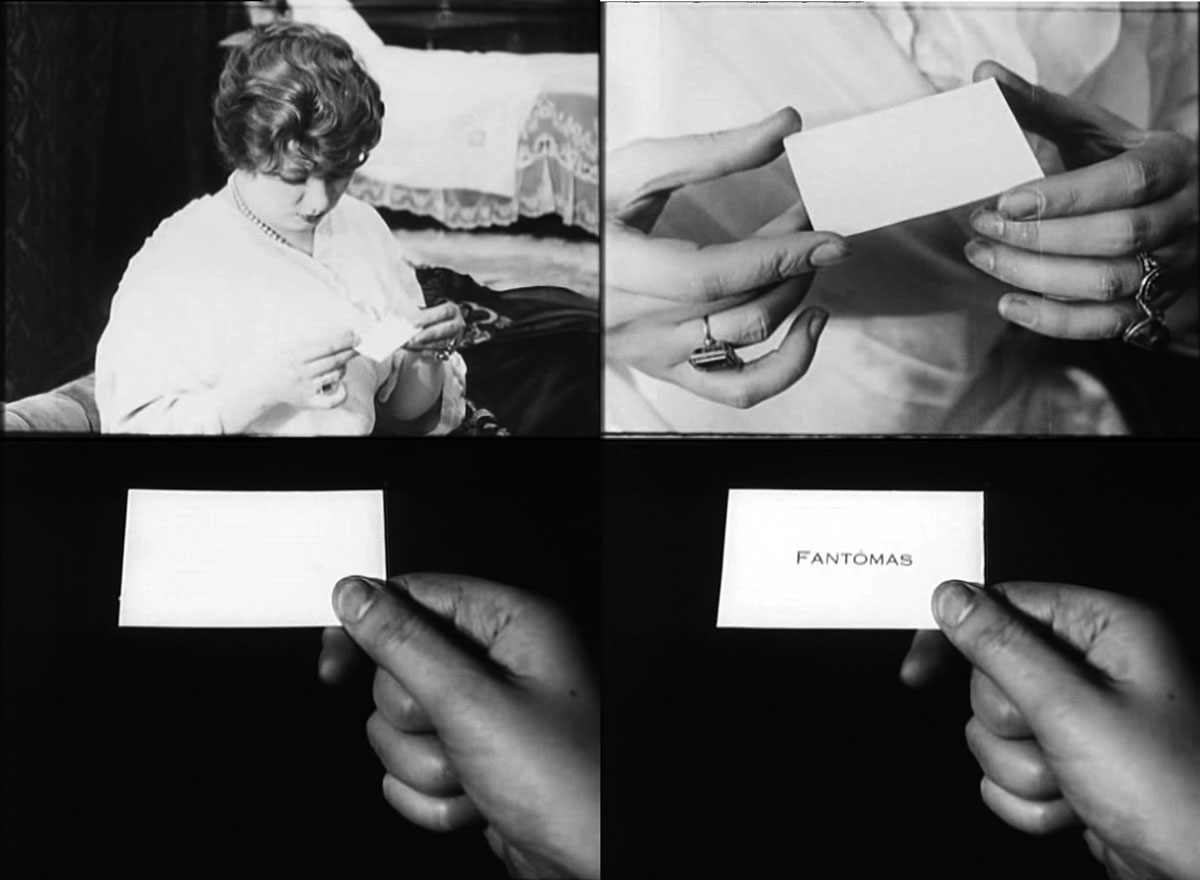

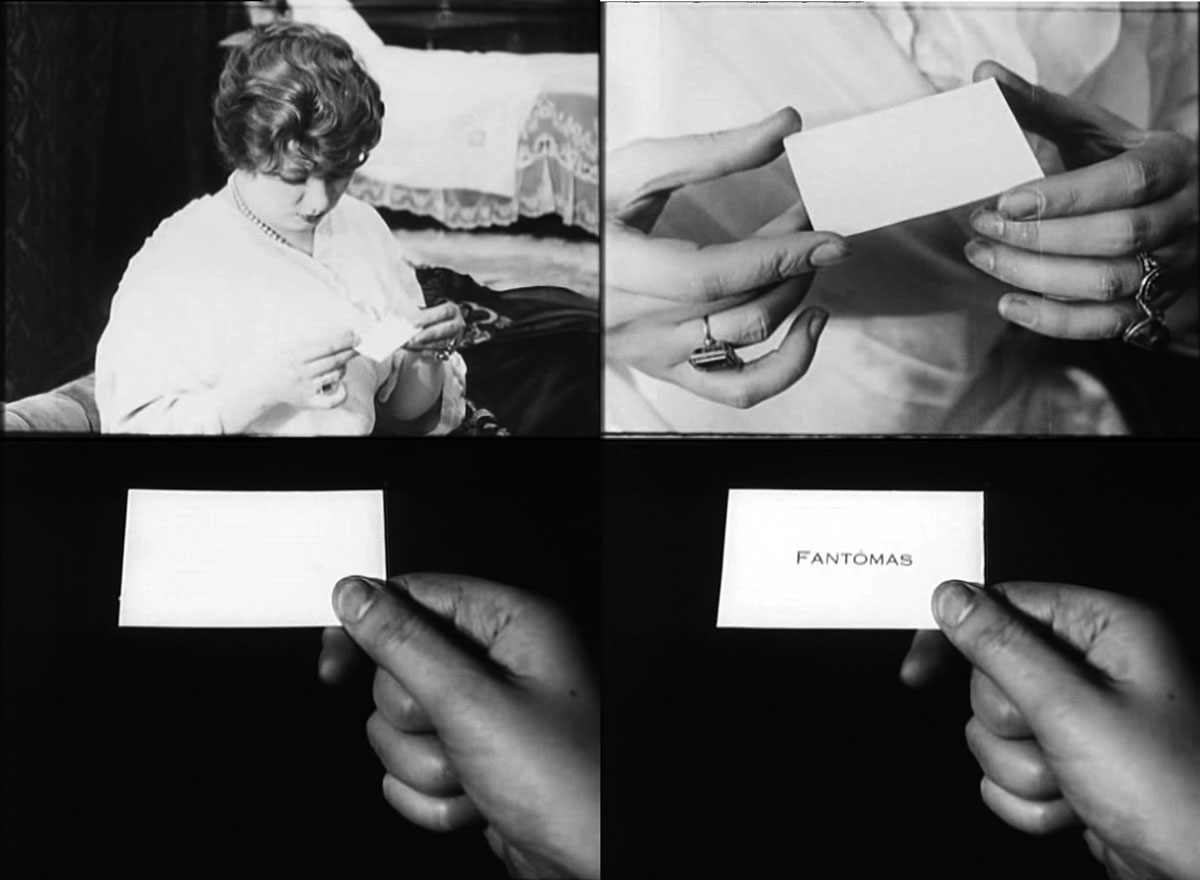

Feuillade’s use of a stationary camera and limited close-up shots established a long, spatial surveillance of the mise-en-scène in which the characters of Fantômas, Juve and the supporting cast would maneuver like fluid props. This was no more brilliantly exhibited than in the very opening sequences of 1913’s Fantômas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine. Feuillade begins the first reel with a beautifully staged robbery at the hotel of Princess Sonia Danidoff, the camera following her continuously through the lobby, along each floor as she ascends in an elevator and into her suite. From behind the curtains the figure of Doctor Chaleck (actor Rene Navarre, to whom we are introduced in an opening montage) leaps upon her with an almost gallant step, demanding her silence with a flick of the finger, then proceeds to pocket her money and jewels. Before exiting he hands her a blank white business card and prays for her continued silence. Feuillade’s camera follows Chaleck as he descends floor by floor to the lobby, mugging and robbing a bellhop of his clothes in the interim. He is able to escape from the hotel undetected before Danidoff calls to report the heist. In a final moment of magic, Feuillade returns to the suite and employs a rare extreme close-up on the white card – in bold, black letters materializes the name “FANTÔMAS.”

Fantômas I - In the Shadow of the Guillotine (1913) - Louis Feuillade

In his use of fluid mise-en-scène, Feuillade was the first to perfect what Bazin called a realist’s la profondeur de champ [“depth of field”]. Rather than concentrate on the disintegration of character and object through a violent temporal redaction which moves the eye continuously, Feuillade maintains the space of the long-shot with every coordinate location being equally dense with possible significance…and ambiguity. As critic David Bordwell has remarked, “Seen from this standpoint, Feuillade becomes a forerunner of Welles, Wyler, Renoir, and the Italian Neorealists.” This use of depth accentuates the hidden caches and stalking villains who play in the chiaroscurist webs of presence and absence as they retreat between foreground and background. This constant shifting of space create multi-planar narratives within each filmed sequence and obscure the differences between characters, objects and mise-en-scène. In Fantômas these ‘planes’ of viewership often supersede the plotted action in their ability to inspire suspense and dread.

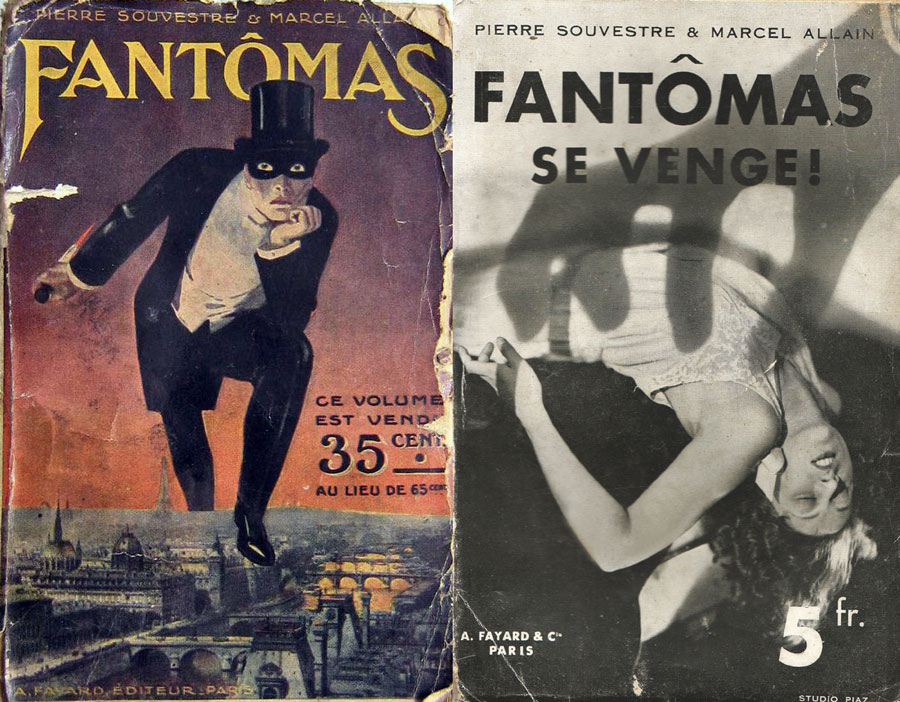

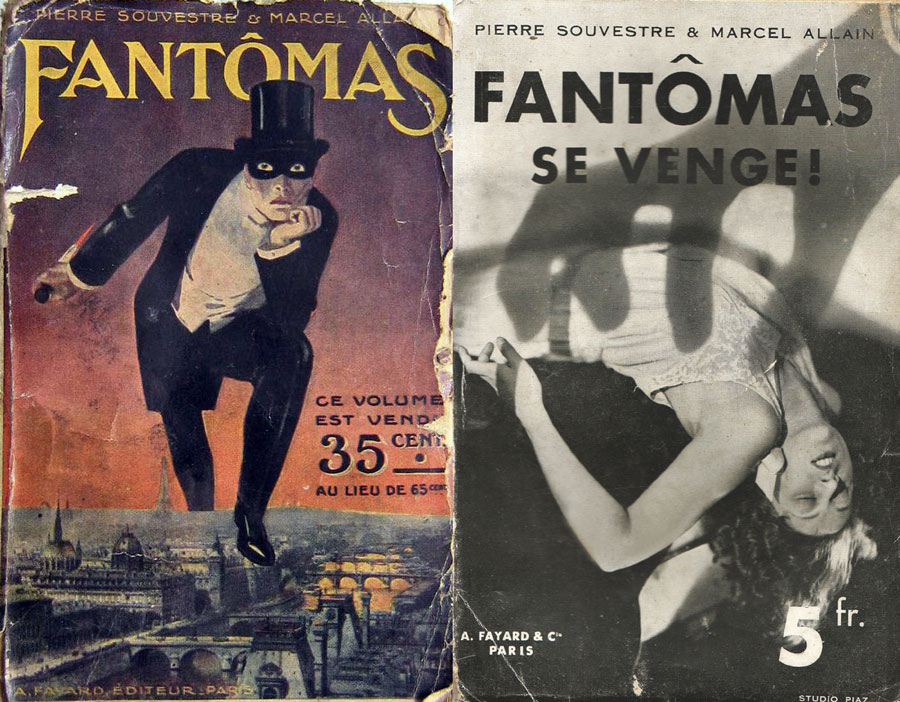

covers of Fantômas (1911) & Fantômas se venge! (orig. 1911) - Allain/Souvestre

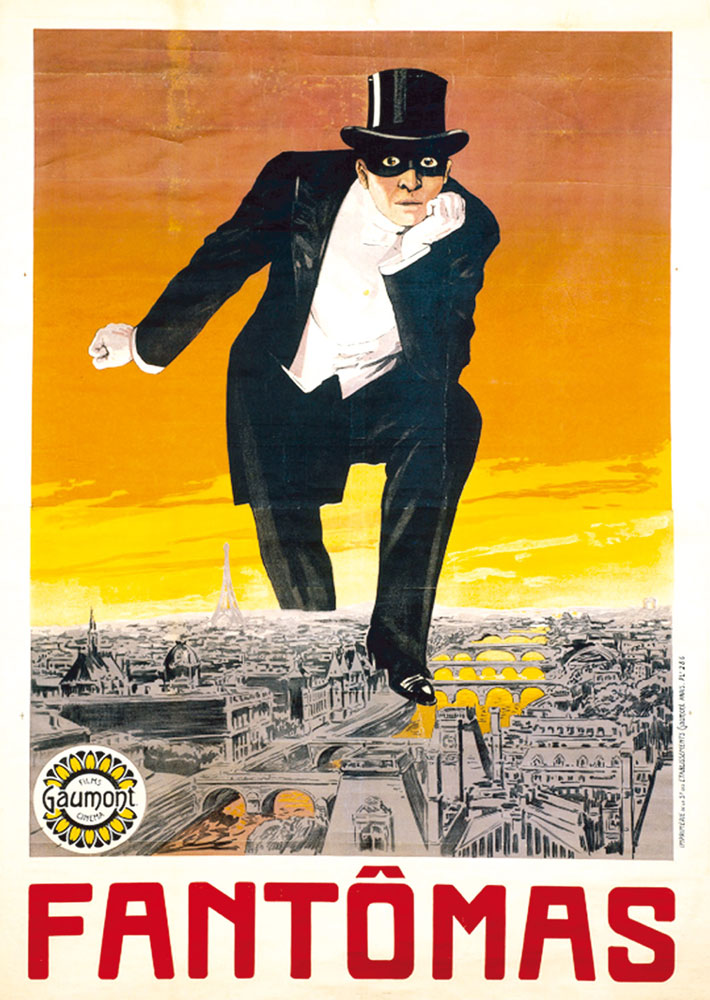

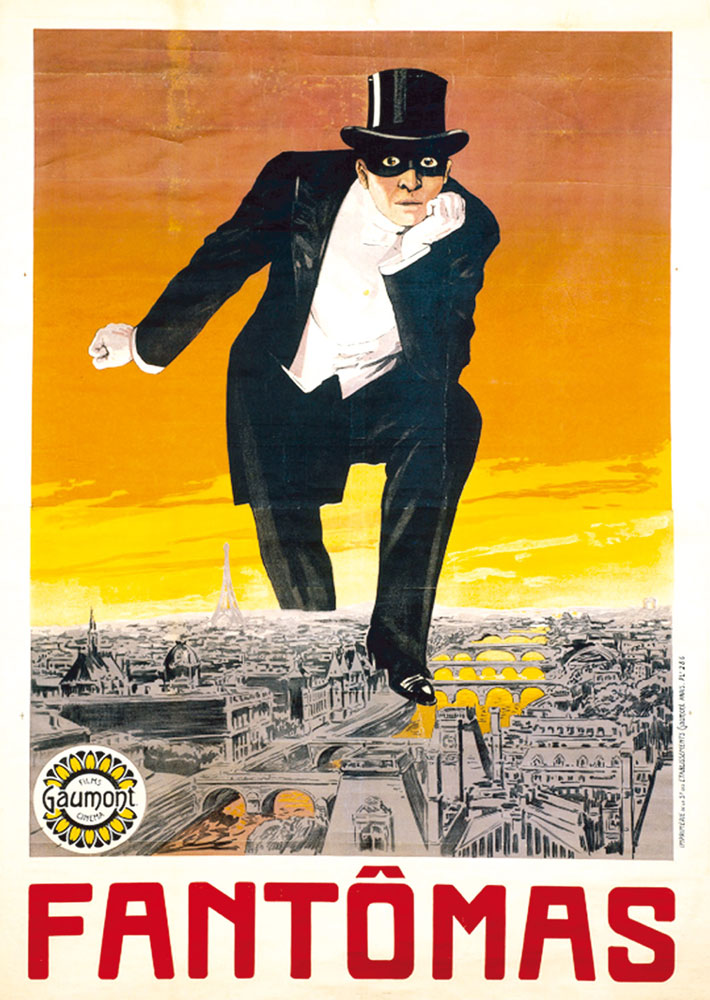

Large portions of the original Allain/Souvestre debut had to be excised for the 54-minute film, including much of the portrayal of the French upper-class that might be considered the only element of social commentary present in the original text. In fact, Allain and Souvestre would attempt to insert transparent, Zola-inspired ribs at the haute-couture of the Right Bank aristocracy in each volume of Fantômas. But to Feuillade’s credit, he cut through the authors’ patronizing Naturalism and instead concentrated on the frequent masquerades of the master of crime as he entrusts himself to Lady Beltham and evades capture by Juve and Fandor. When Fantômas is finally apprehended and sentenced to death, Feuillade uses the brilliant sub-plot of Valgrand’s (an actor who has a striking resemblance to the prisoner) vain folly to spring the criminal from Santé at the last moment. In the closing moments of the film, a tortured Juve sits in his office at the precinct, imagining the elusive Fantômas disguised in black tie, top hat and mask appearing before him, teasing him to his feet only to dematerialize in his grip like a Méliès apparition.

The first Fantômas was released on 9 May 1913 at the massive Gaumont-Palace as a French cinematic event. As Jacques Champreux writes, “The triumph was immediate…An official statement published in the Petit Journal advertised the unbelievable figure of 80,000 spectators in a week…” But the theater-going public’s hunger for this cinema of crime did not often extend to the bourgeois circles who were increasingly looking to the American epic film—with its emphasis on characterization, plot development and pathos—as the standard-bearer for cinema-as-art. For them, Feuillade’s Fantômas was nothing more than a serial-come-to-life, a retrogressive display of violence and senseless thrills.

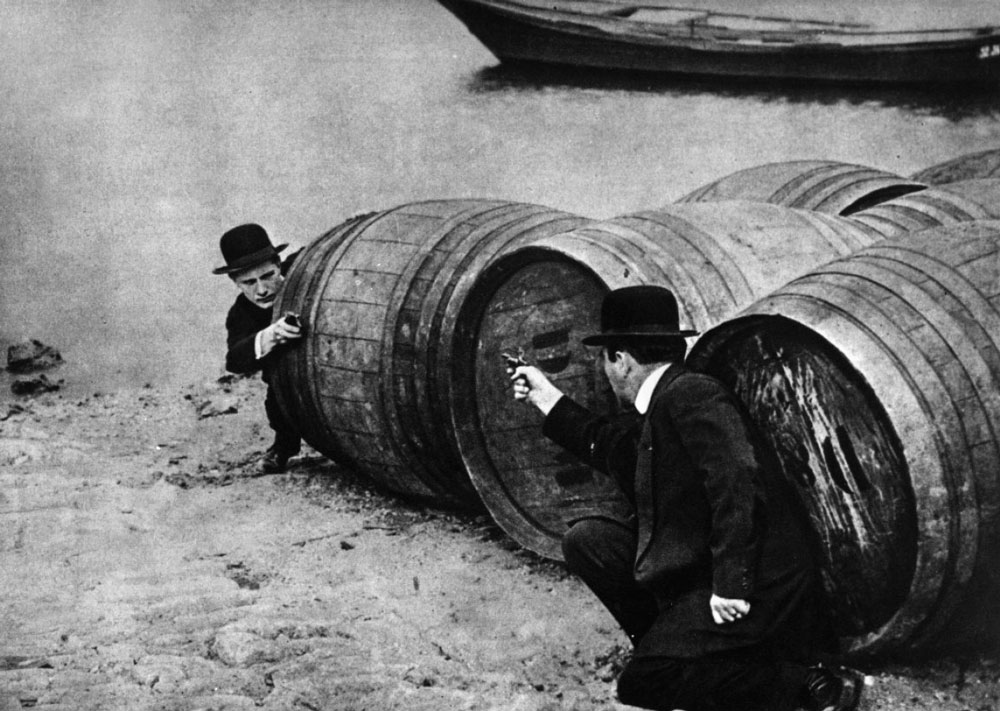

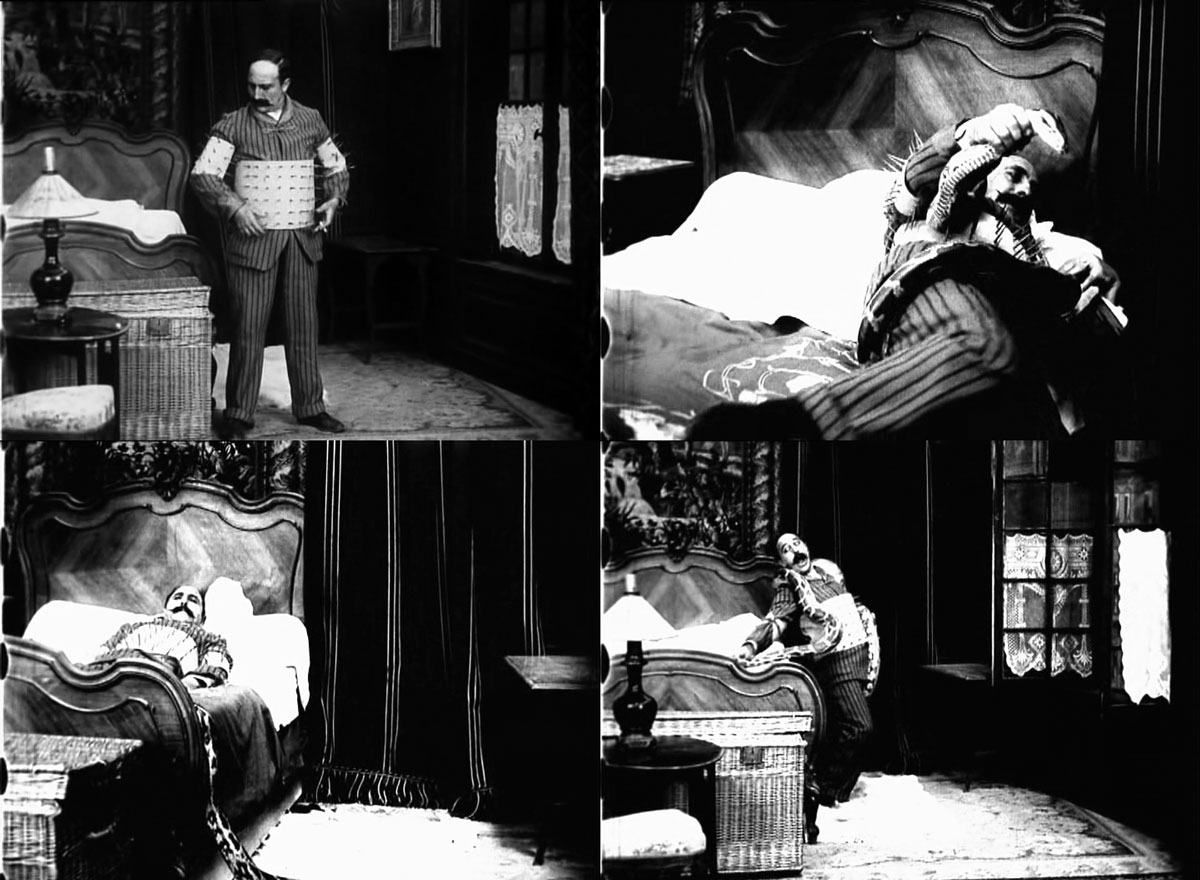

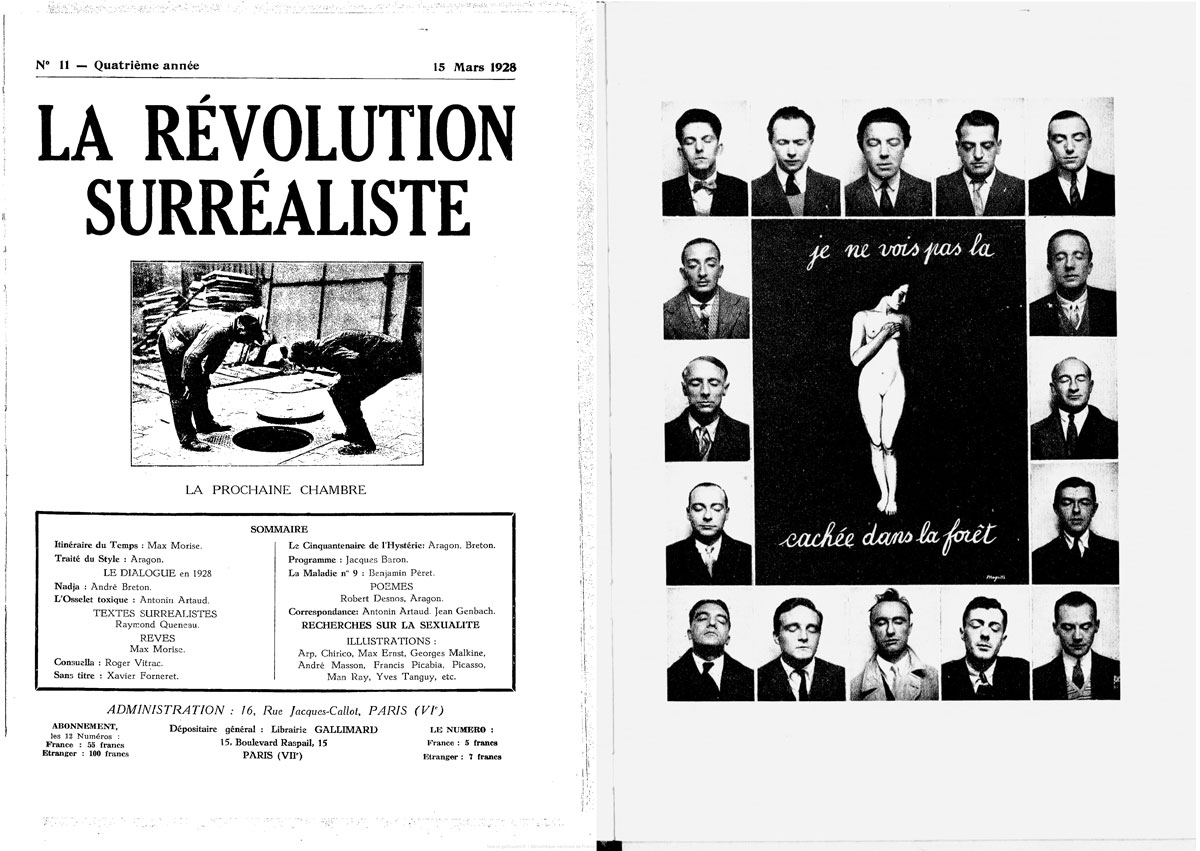

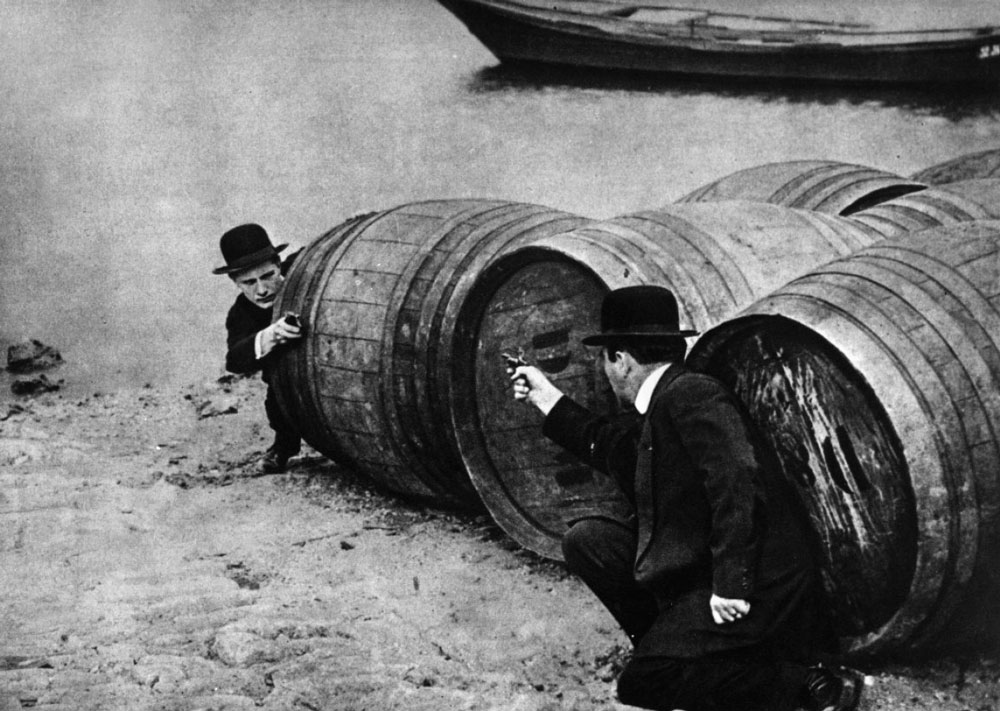

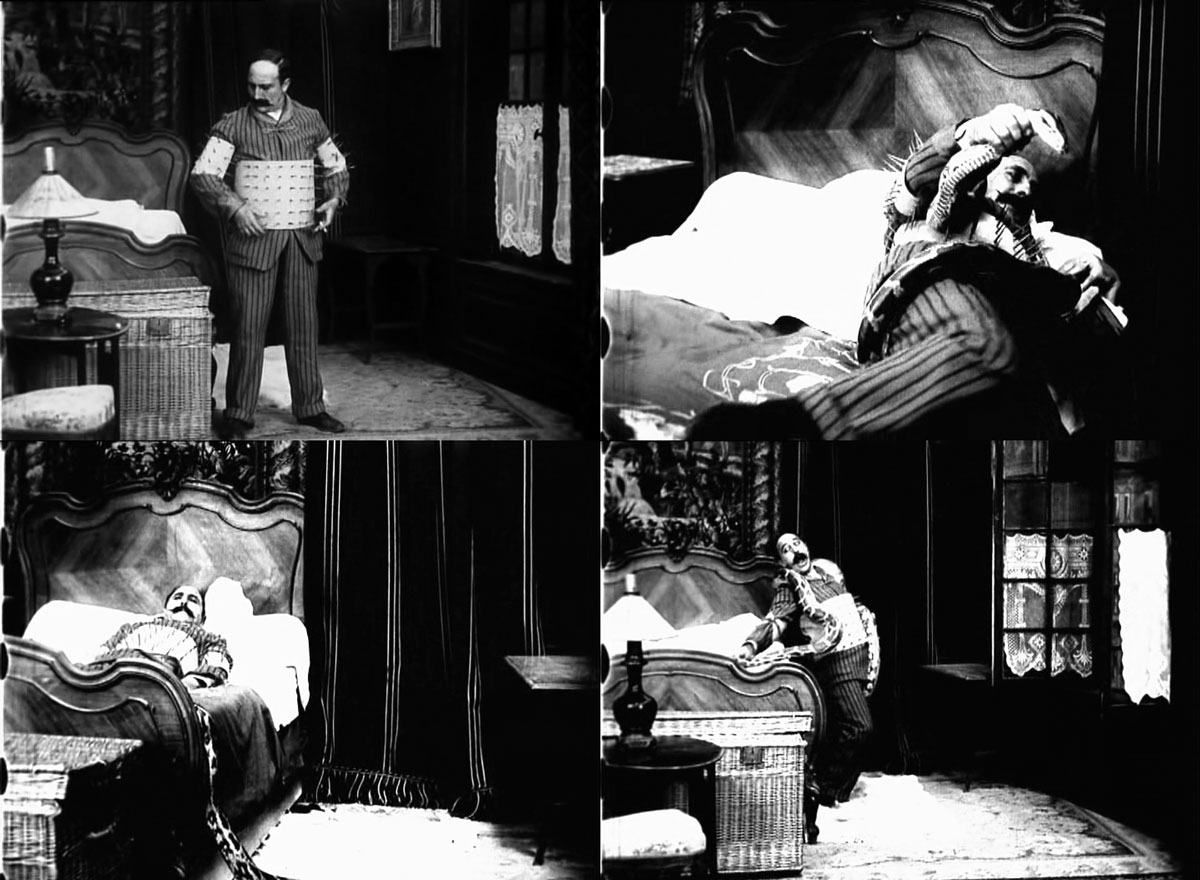

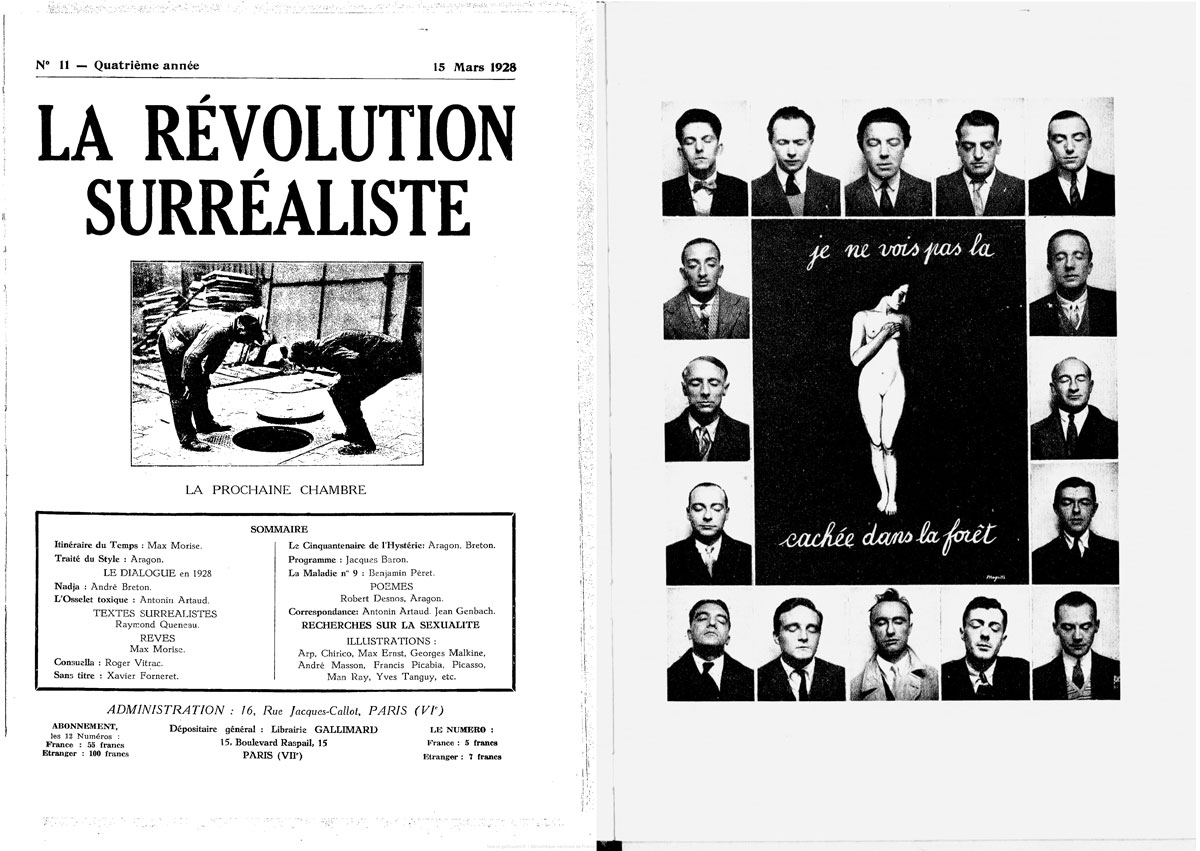

With each successive installment of the Fantômas films, Feuillade expanded both the visual language of the mise-en-scène and the spectacle of violence. In Juve Against Fantômas a foiled train robbery at Gare de Lyon hatched by Loupart—another disguise employed by Fantômas—and his newest mistress Joséphine-la-Pierreuse ends with a tragic derailment and explosion, killing hundreds of passengers. When Fantômas decides to murder Juve in the middle of the night, he releases a boa constrictor into his room to execute the deed. The inspector, who has learned of the plot but not of the method, covers his body with metal spikes. The ensuing bizarre melee between Juve and the snake is a model par excellence of sadomasochistic transgression. The psychosexual motif extends to the first glimpse of Fantômas en cagoule, covered from head to toe in a tight black bodysuit, a nihilist’s shroud which inverts the usual campish fashion and counterfeit costumery of the master of disguise. In one of the most disturbing images of the film, this creature swathed in his black raiment extends and writhes his body in a weird sign of victory after detonating a bomb meant to kill Juve and Fandor.

Fantômas II – Juve Against Fantômas (1913) - Louis Feuillade

Fantômas II – Juve Against Fantômas (1913) - Louis Feuillade

The Murderous Corpse finds Fantômas navigating through claustrophobic interiors to commit another series of murders and heists. The titular crux of the episode revolves around a particularly gory ruse whereby the villain has graduated from disguising his identity with clothes to human skin. His ensuing crimes are then attributed to a man whose mangled corpse has been left in the sewers. Princess Sonia Danidoff reappears just long enough to be re-victimized by Fantômas. Her fiancé, M. Thomery, is then lured by Lady Beltham to the hideout of Fantômas, where his newly acquired band of outsiders, all clothed en cagoule, kill the intruder in the film’s most infamous scene. Throughout the initial five reels of The Murderous Corpse the fate of Juve has been left unresolved, leaving Fandor on his own in tracking and capturing Fantômas. In fact, Juve has outmaneuvered his nemesis and infiltrated the inner circle only to reveal himself in the final reel in order to save Fandor. To heighten the sense of indeterminate spaces and psychotopological dread that infuses The Murderous Corpse Feuillade uses various odd angular shots and mutable stage sets. When Fantômas disappears into a hidden passageway at the film’s conclusion, it seems that Feuillade has reified the intense labyrinthine play to which he has subjected the viewer for nearly 90 minutes. With its emphasis on mise-en-scène, ambience and suspense, Feuillade’s lens invokes the dense phenomenologies of writers Jorge-Luis Borges, Maurice Blanchot and Raymond Roussel, arguably making The Murderous Corpse the most inventive and rewarding member of the serial.

Fantômas III - The Murderous Corpse (1913) - Louis Feuillade

In Fantômas Against Fantômas, suspicion is mounting that Juve himself is the nefarious villain. At the film’s opening, he is taken into custody and once again it’s up to Fandor to capture Fantômas and prove his friend’s innocence . Meanwhile, Fantômas employs another prop-bag of false identities—including the superannuated Pere Moche and the hilariously named American inspector Tom Bob—to stage a charity ball in his own honor. Aside from the beautiful sequence where three hooded figures enter Lady Beltham’s villa and only two exit, there is also a vividly gory moment in the first reel that has Tom Bob discovering a corpse hidden in an apartment crawlspace by way of a bleeding wall. The ongoing theme of ambiguous identity is further compounded as Fantômas foists another anatomical ruse upon Juve and nearly convinces the police chief of the inspector’s complicity. The narrative of Fantomas’ apaches – the criminal syndicate that surrounds him – is expanded here as is the number of the gang itself until it is quite pathologically portrayed to be an invisible world order of chauffeurs, bums, shopkeepers, streetwalkers, gendarmes and more, all carrying out Fantômas’ most quotidian whims and ensuring his freedom.

***

Allain and Souvestre together completed 32 volumes of the Fantômas serial, concluding with the villain’s death in The End of Fantômas. Their collaboration would certainly have continued had it not been for Souvestre’s untimely death during a Spanish influenza outbreak in the early winter of 1914. Allain would later resuscitate his most popular character and continued writing Fantômas sporadically from 1925 until 1963, completing 43 volumes in total and another 400 volumes comprising other serials. In an odd postscript, he would also marry Souvestre’s longtime girlfriend, Henriette Kistler, in 1926.

But it was not in the original compositions of Allain and Souvestre, nor in the film adaptations of Feuillade, that Fantômas would achieve his greatest notoriety and take on his most influential role. When the popularity of Fantômas was at its height just prior to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the master villain’s most important influence was measured neither in mass public reaction nor in bourgeois critical circles, but in the inspiration the serial had given to a new generation of poets, painters and philosophers living and working in the outskirts of Paris. It was here, amidst the renegade artistic movements blossoming in the cooperatives, cafés and galleries at the north and south ends of Paris, in the Montmartre workshop of Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire and at the bustling cafe tables of La Closerie des Lilas, La Coupole and Le Select, that Fantômas would become less entertainment and more a radical totem of twentieth-century psychic revolution. For the artists suspended above the void of total military destruction, Fantomas was recognized as a figure of sublime beauty and horror, a black-clad urban phantom, an oracle foretelling the grand-guignol of War. To these first generation groups, alternatively labeled Cubists, Fauvists, Surrealists, Dadaists and Futurists, the nightmarish visage of Fantômas—whether in dainty masquerade or hooded like an executioner—was the modern, industrial incarnation of 19th century-Europe’s various anti-heroes: Sade’s libertine, Maturin’s Melmoth and Lautréamont’s Maldoror.

Pablo Picasso, Moise Kisling and Paquerette at the Café de la Rotonde in Paris (1916) - photo by Jean Cocteau.

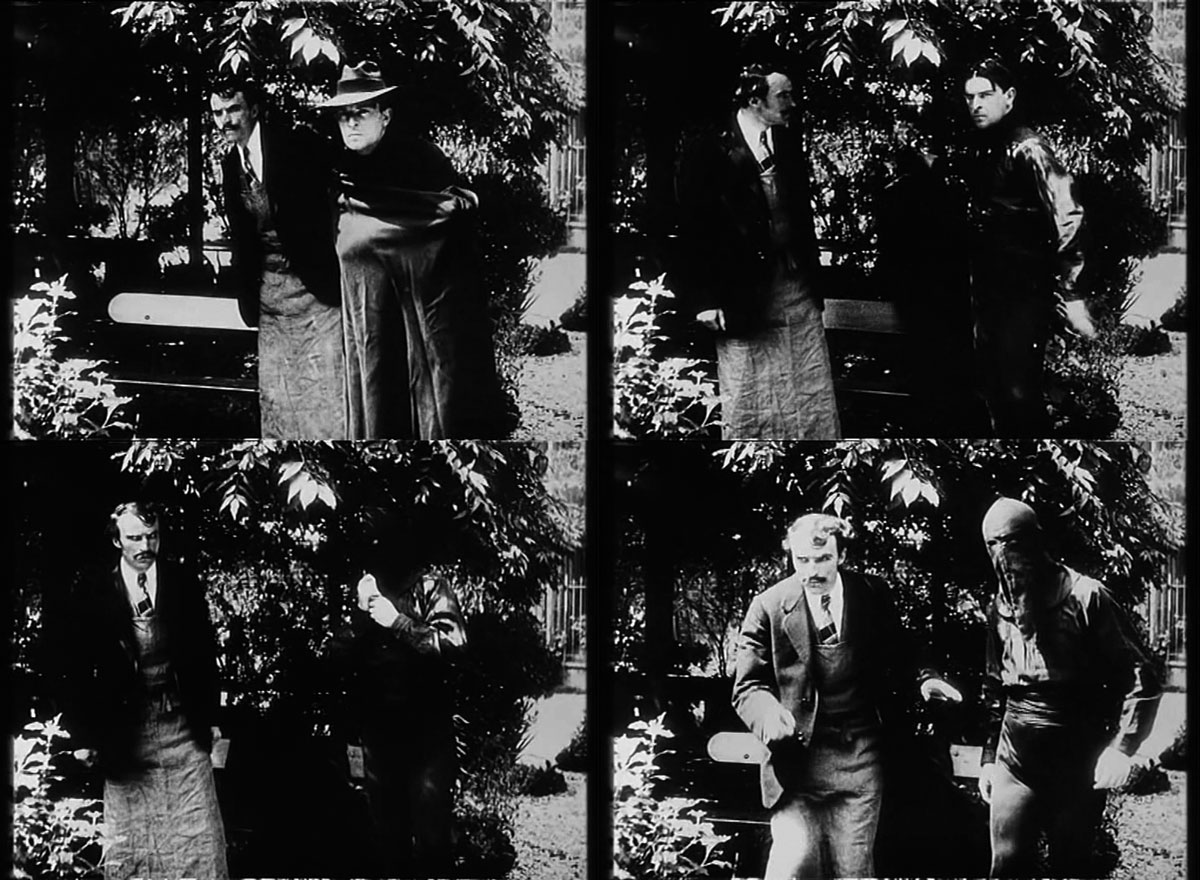

Here Fantômas, an objet d’art, transcends the social milieu of its origin and becomes reformatted according to the ideology of a new petit bourgeois art movement. For despite the representation of Fantômas as a renegade or iconoclast of middle-class law, the political backgrounds of his creators, Allain, Souvestre and Feuillade were entrenched in the established conservativism of the State. All three shared Catholic and monarchist sympathies that were quite opposed to the revolutionary ideology of the avant-garde. This gap in ideologies was indicative of the large spectra of political allegiances that dominated French, and particularly Parisian daily life, on the eve of the First World War. But its origins had been years in the making. From the humiliating loss of the Franco-Prussian war to Otto von Bismarck’s powerful German army, the bloody riots of the Paris Commune and the foundation of the Third Republic in 1871, France had been marked by a persistent national identity crisis propelled, in part, by a gaggle of rival political parties who vied for control of the government. “Ah, what a cesspool of folly and foolishness, what preposterous fantasies, what corrupt police tactics, what inquisitorial, tyrannical practices!” wrote Emile Zola of the state’s rampant injustices at the turn of the century. “What petty whims of a few higher-ups trampling the nation under their boots, ramming back down their throats the people’s cries for truth and justice, with the travesty of state security as a pretext.”

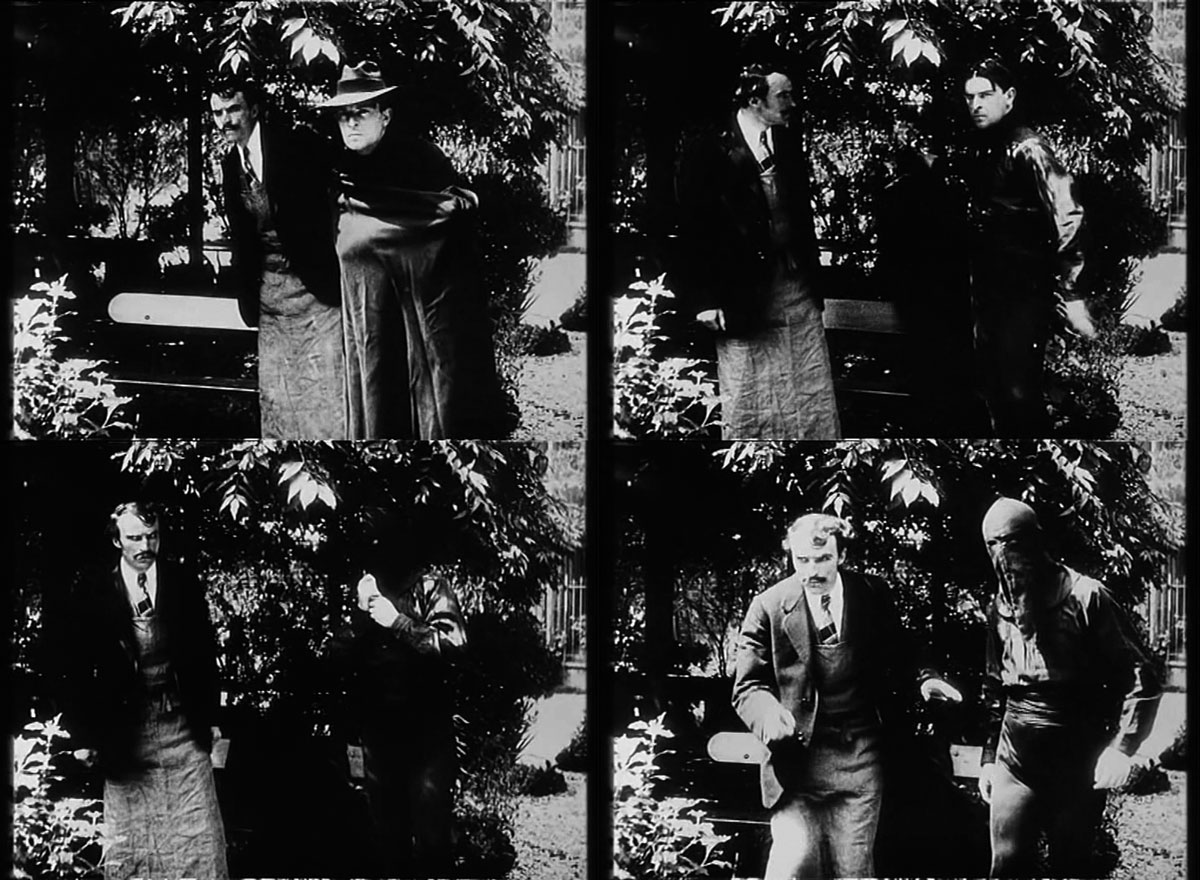

Zola’s political sentiments reached a crescendo during public scandals like the Dreyfus affair which exposed the factionalism and racism of a divided country. Falsely charged with treason and publicly cashiered from the army, Captain Alfred Dreyfus – a highly decorated soldier and Jew – became a cause célèbre for both conservatives and radicals. In response, party lines across the city tightened with an increasing intellectual intolerance. The Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO), the prominent socialist party mounted a major propaganda campaign against Action Française—led by the Catholic monarchist Charles Maurras—who had been largely responsible for inciting the public condemnation of Dreyfus. Maurras’ popularity rested on a prevalent French xenophobia which blamed the quatre états confédérés [“four confederated states”]—Jews, Protestants, Freemasons and immigrants —for the loss of the Prussian War and the rise in liberal ideology. For Maurras, these quatre états confédérés were proof that the effects of the Revolution had to be reversed if France were to be saved.

The Third Republic was also the age of the so-called apache. “A crime reporter for Le Journal, Arthur Dupin, had first used the term ‘apache’ to embellish his accounts of Paris street gang rivalry in 1902 and it soon became a code word for the urban criminal activity allegedly threatening French lives and property,” writes Richard Abel in The Thrills of Grande Peur: Crime Series and the Serials of the Belle Époque. As if to add insult to social injury, roving apaches, also known as mauvais garcons, would often adopt the sobriquet of the era’s most popular villain when committing their crimes, so that real robberies, muggings, and murders would often be blamed on a seemingly ubiquitous Fantômas. The phenomenon would recur so often that by the release of Feuillade’s next serial Les Vampires—a gothic tale of a murderous Parisian gang led by their sultry dominatrix, Irma Vep—the city government would institute a temporary ban on his films. Assassination, political intimidation and gang warfare were all common practices used on both the left and right to ensure territorial victory. In this environment the murder of SFIO leader and antimilitarist Jean Jaurès just days before mobilization against Germany had the very senseless fingerprint of Fantômas.

The first artistic flirtations with Fantômas came with Apollinaire’s July 1914 review of the Allain/Souvestre serial in the literary review Mercure de France, where the perpetually overzealous writer baptized the work an “…extraordinary novel, full of life and imagination...from the imaginative standpoint, Fantômas is one of the richest works that exist.” If this was the first call for the apotheosis of the serial character, it would certainly not be the last. Apollinaire’s absolutist and inflammatory declaration incited his fellow artists from Montmartre and Montparnasse to match his loquacious prose. In an August edition of Les Soirées de Paris, Apollinaire collaborator Maurice Raynal wrote of Feuillade’s Fantômas, “And now, dare I or don’t I? Well, take courage and trust in the grace of God. Now… Fantômas! What nobility! What beauty! It’s one of those things that stuns you; its serene majesty, like inimitable brilliance, leaves you breathless, dazed and mute…It is like the best of Hugo, and more beautiful in fact!” In Max Jacob’s 1916 collection Le Cornet à dés [The Dice Cup], the Montmartre eccentric includes a playful lyric of two gourmands’ unlikely encounter with the master villain in “Encore Fantômas.” Soon other outspoken writers would add their kudos, throwing their hats into an ever-widening ring of “Friends of Fantômas.” “Absurd and magnificent lyricism,” claimed the cravat-and-laced dandy Jean Cocteau. “The modern Aeneid” countered poet and essayist Blaise Cendrars. Even James Joyce was a follower, penning a typically Joycean neologism “Enfantomastic” to describe his adulation.

Fantômas (1915) - Juan Gris

Painters and sculptors experimenting in the burgeoning cubist style found in Fantômas a dark, foreboding icon they could insert, scatter and deconstruct upon the canvas using the ‘poetic’ methods of collage and decoupage. Juan Gris’ 1915 painting Fantômas (Pipe and Newspaper) centered on the bricolage of a café and included a copy of the serial novel among the scattered objects. Yves Tanguy, a friend of surrealist poet Jacques Prévert and an eventual ally of Andre Breton, produced an homage to the master of crime in 1925 using the angular, biomorphic styles of Giorgio de Chirico and Salvador Dali. (“Even in an atypical ‘literary’ painting such as this, no very accurate reading is possible,” wrote John Ashbery of the piece in 1974. “Space and perspective are methodically distorted; it is impossible to gauge distances by the size of the figures, and there is some iconography…which seems not to relate to the story of Fantômas. The stage seems set for the radical transformations which will very shortly sweep it almost bare.”) In a 1966 article for Film Commentary entitled “Early Surrealist Expression in the Film”, Georges Sadoul recounts in an interview with critic Toby Mussman, “…how he, Jacques Prévert, Yves Tanguy, and [writer] Raymond Queneau would spend whole evenings discussing their knowledge of the various episodes of the Feuillade serials….”

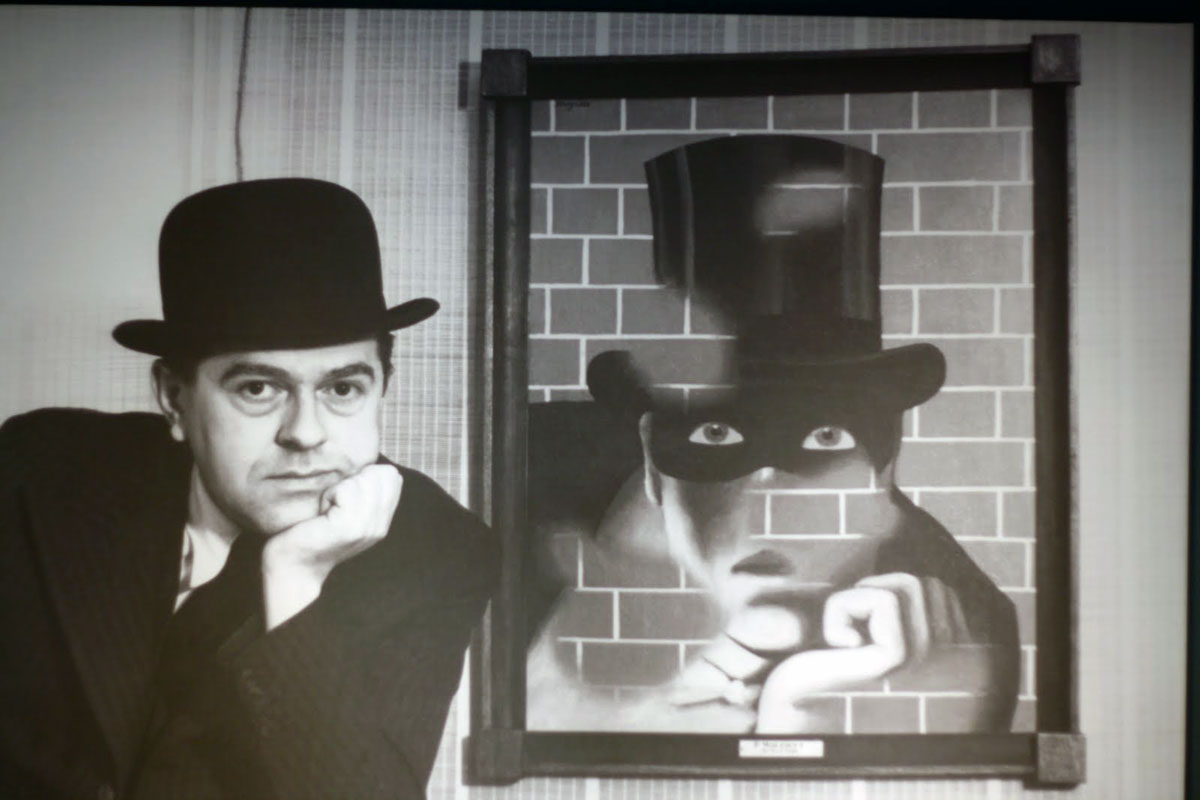

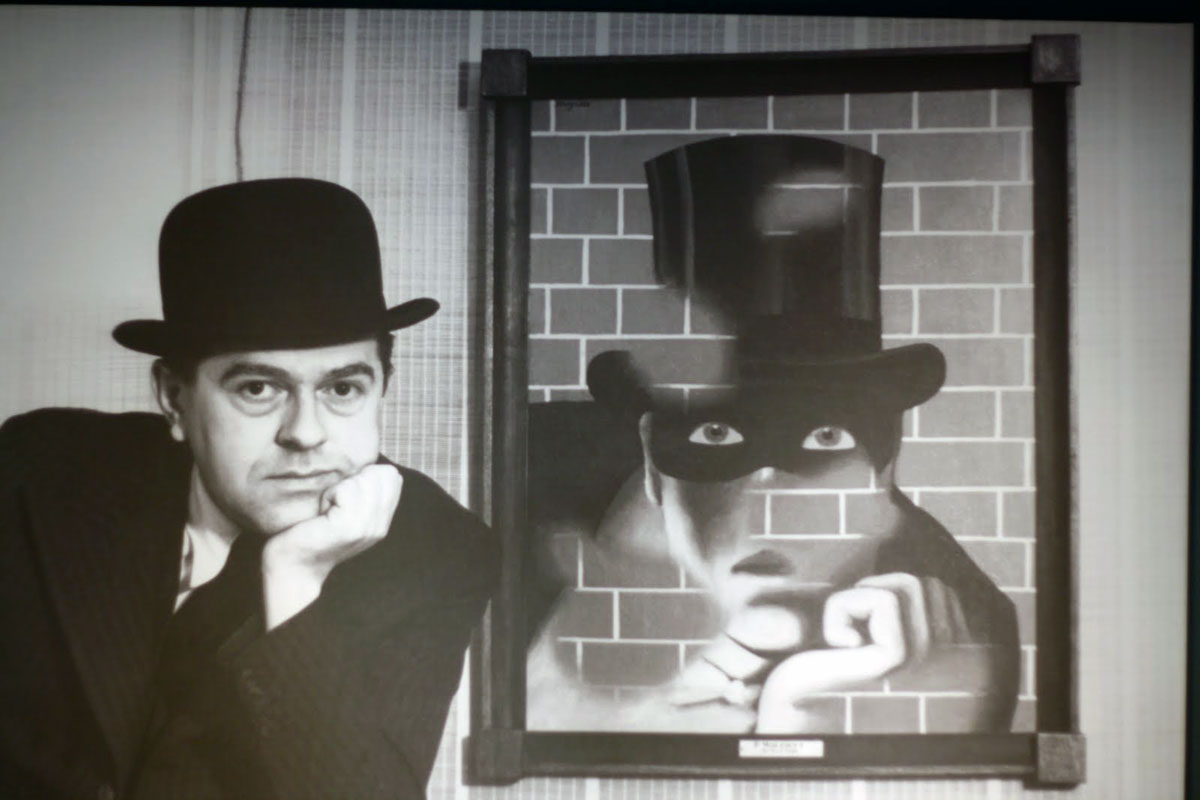

Belgian expatriate René Magritte employed Fantômas as a subject throughout his work in the ’20s. In his 1926 L’assassin menacé (The Menaced Murderer) Magritte reproduces a famous “depth of field” image from The Murderous Corpse where two members of Fantômas’ gang lie in wait against a doorway, preparing to commit their nefarious deed. Beyond the cinematic images of Rene Navarre’s character, Magritte used Gino Starace’s serialized covers to great effect. For example, 1928’s Le barbare (The Barbarian) is a trompe l’oeil that uses a Starace-inspired Fantômas camouflaged amid the tessellations of a brick wall. And in 1943’s Le retour de flamme (The Return of the Flame), Magritte uses Starace’s iconic landscape of Paris with the masked villain stepping over the Eiffel Tower. So immersed was Magritte in the novels and Feuillade films that he would once tell an interviewer, “I am Fantômas.”

Fantômas III - The Murderous Corpse (1913) - Louis Feuillade

L'assassin menacé (1926) - René Magritte

The first legitimate cult dedicated to the master of crime appeared in Montmartre in 1913. Despite its impressive and oblique title, the “Society of Friends of Fantômas” (SAF), as it was initially called by founder Apollinaire, was no more than a loose cadre of artistic apaches who lacked any central manifesto or political agenda. But as a precursor to Dada and the Surrealist movements by more than five years, the SAF proved essential as the initial rebel yell for the young, dispossessed artists living in the northern banlieue. And Fantômas was to be their totem.

The foundation of the SAF also lied in Apollinaire’s personal connections with the Cubist school established by Picasso and Georges Braque (also SAF members) between 1908 and 1911. The SAF headquarters was located at Picasso’s workshop near the Sacré-Cœur Basilica and the Moulin Rouge, the infectious center of Montmartre’s bohemian enclave. Thousands of poets, painters, musicians, critics, dancers, grifters, thieves and flaneurs called the neighborhood between the Butte Montmartre and the Rue Pigalle their home and stomping ground. It was here that the poet/dandy Jean Cocteau would meet Picasso and form an immediate artistic bond that would last nearly half a century. It would also provide Cocteau entrée into the underground art world inhabited by composer Erik Satie, Russian director Serge Diaghilev and Blaise Cendrars. So wild and licentious were the days and nights of Montmartre, with its cabarets, brothels, saloons and opium dens, that it singularly defined the French term demi-monde (“underworld”) as a nexus of crime and artistic invention. But its riotous extremes were not limited to the northern end of Paris. In 1911, when Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was pilfered from The Louvre in what the police considered an “inside job”, the conspiracy led straight from the Seine to Picasso’s workshop. Apollinaire and Picasso were both arrested on suspicion and hauled in front of a magistrate at the Palais de Justice for questioning. They were eventually exonerated for lack of evidence.

If the artists of the SAF romanticized a certain conceptual violence which they grafted onto the page or canvas as an act of cultural rebellion, the dizzying bloodshed of war may have come as a bitter reward indeed. With the arrival of la grande guerre in August 1914, many of Montmartre’s artists and poets were mobilized on the Eastern front or fled Paris to avoid conscription. Picasso was drafted by the military to produce large simulated canvases of French soldiers and foliage to confuse the German invaders in the trenches. Cocteau was a medic on the Belgian front but fortunately shuttled back and forth to Paris regularly and saw little action by the war’s end. Others were not so fortunate. Apollinaire suffered a massive head wound from flying shrapnel in 1916 and was decommissioned shortly thereafter. The complications from the hematoma would cause the poet severe pain and dizzy spells until his death in 1918. Fernand Léger, another cubist-inspired painter, nearly died during a mustard gas attack at Verdun. Poet André Breton spent the war caring for patients in a neurological ward in Nantes. There he would meet one of his greatest Surrealist inspirations, Jacques Vaché, a writer and Pere Ubu eccentric who would tragically kill himself in 1919. Other young poets and painters, like Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia left for America before the war began, outraging many of the pro-French artists who were determined to fight for their homeland.

_at_the_Th%C3%A9%C3%A2tre_du_Ch%C3%A2telet%2C_Paris%2C_1917%2C_Lachmann_photographer.jpg)

Pablo Picasso and scene painters sitting on the front cloth

for Léonide Massine's ballet Parade, staged by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes

at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris (1917) - photo : Lachmann

In spite of the massive physical and psychological destruction incurred in Calais and the Ardennes in 1916-17, life among the Montmartre vanguard continued in Paris at a fever pitch. One of the most notorious cultural events to echo across the city during the height of the war came with the performance of Parade at the Théatre du Chatelet. Purportedly developed by Cocteau in response to dance director Serge Diaghilev’s daring words “Etonne-moi!” [“Astonish me”], Parade was a carnivalesque spectacle filled with jugglers, acrobats and ragtime dancers. Premiering in May 1917 with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, music by Erik Satie and stage sets by Picasso—all members of the SAF—Parade was one of the earliest synergistic collaborations of the Cubists and surrealists. In fact, the term surrealism was first coined in the performance playbill by a crippled Apollinaire who wrote that Parade was “une sorte de surréalisme”. So divisive was its debut that Parade is often compared in notoriety to the 1913 performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring which caused riots across Paris. “If it had not been for Apollinaire in uniform,” wrote Cocteau of the evening, “with his skull shaved, the scar on his temple and the bandage around his head, women would have gouged our eyes out with hairpins.” The imagined scene of mayhem recalls nothing short of the most violent purges of Fantômas.

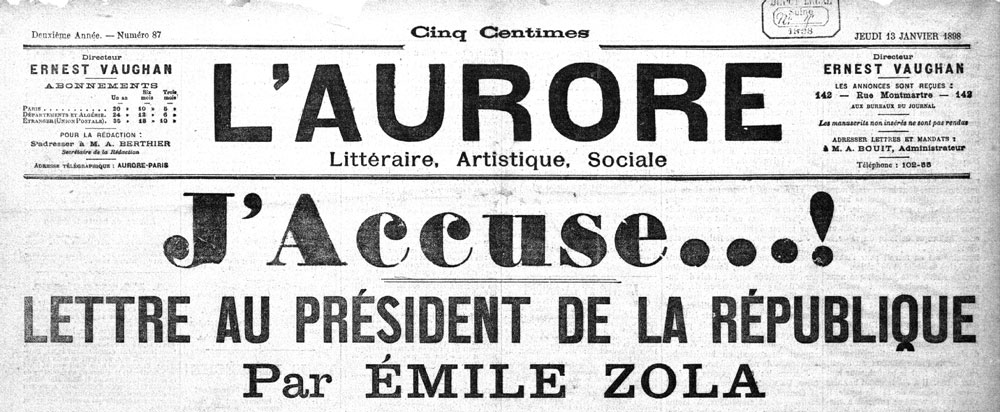

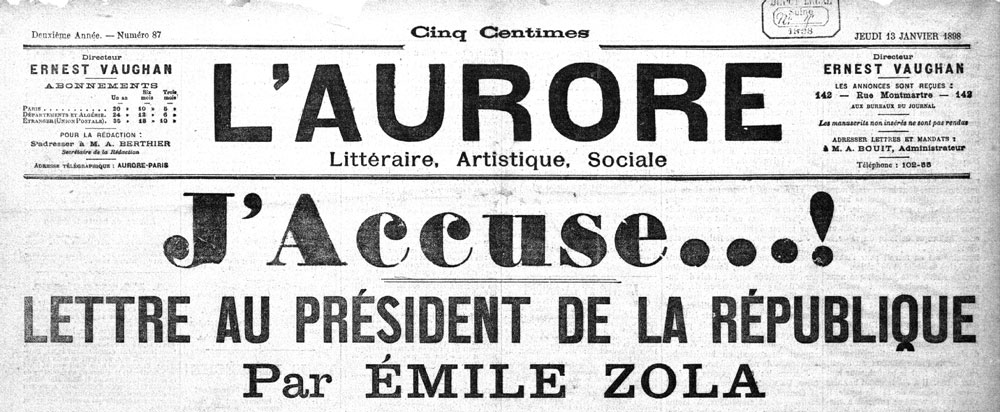

La révolution surréaliste (March 1928 - Dec. 1929)

The predominantly French surrealism movement was developing in tandem with its more outrageous Swiss cousin, Dada. Dada’s first public recitation had come in July 1916 at Zurich’s infamous Cabaret Voltaire and resident theoretician Tristan Tzara published his earliest manifesto two years later. When the regulars of the Voltaire dispersed at the conclusion of the War, Tzara traveled to Paris where he discovered compatriots Apollinaire and Breton waiting anxiously for his arrival. But it was Breton and not Tzara who would take the reins from Apollinaire after his untimely demise in the influenza pandemic of November 1918. Breton had already begun to amass a newer generation of young writers and aesthetes and, with their support, easily slipped into the ceremonial position left vacant at Apollinaire’s death. In the following year Breton, Aragon and Soupault debuted their own ‘surrealist’ magazine Littérature and a collaborative novel Les Champs Magnétiques [The Magnetic Fields] – published in 1920 – was the first piece credited to the automatic writing technique and officially licensed by Breton as surréalisme. “Surrealism will usher you into death, which is a secret society,” wrote Breton in 1924’s Le Premier Manifeste du Surréalisme. “It will glove your hand, burying therein the profound M with which the word Memory begins.” In a profound evocation of the SAF and the mysterious violence of its idol, the proported tenets of surrealism claimed its raison d’etre to be a celebration of the le merveilleux quotidien [“the everyday marvellous”] and its individual corollate, the ‘un’conscious. What Dada had instigated as a reactive, anti-Art campaign against the traditional, bourgeois valuations of aesthetics and class, surrealism had expanded upon with a neoteric regimen of Freudian analysis, Hegelian dialectics and radical politics. Breton’s infectious distillation of art and philosophy might well have driven those unaffiliated artists around him to join his ranks in the beginning – including artists from the rue Blomet and the rue du Château and the so-called Grand Jeu – but it was this very rigid idealism that would make of them mavericks. Despite what he had claimed as a surrealist aphorism par excellence – “The exquisite corpse drinks the new wine…” – Breton’s celebration of the narrative of the body was tempered with an increasing dependence on psychoanalysis and Marxist politics. His descriptions of the marvellous had always favored chance and random juxtaposition, neurosis and the dream-state, but refused to negotiate the more sinister categories of excess and atrocity – desire, violence and death. When Breton allied himself with the French Communist Party in ’27 amid an ultra-militarized left the focus of surréalisme became a political rather than aesthetic Revolution. All notions of literary and artistic decadence, primitivism and hermeticism were excised and condemned within the group.

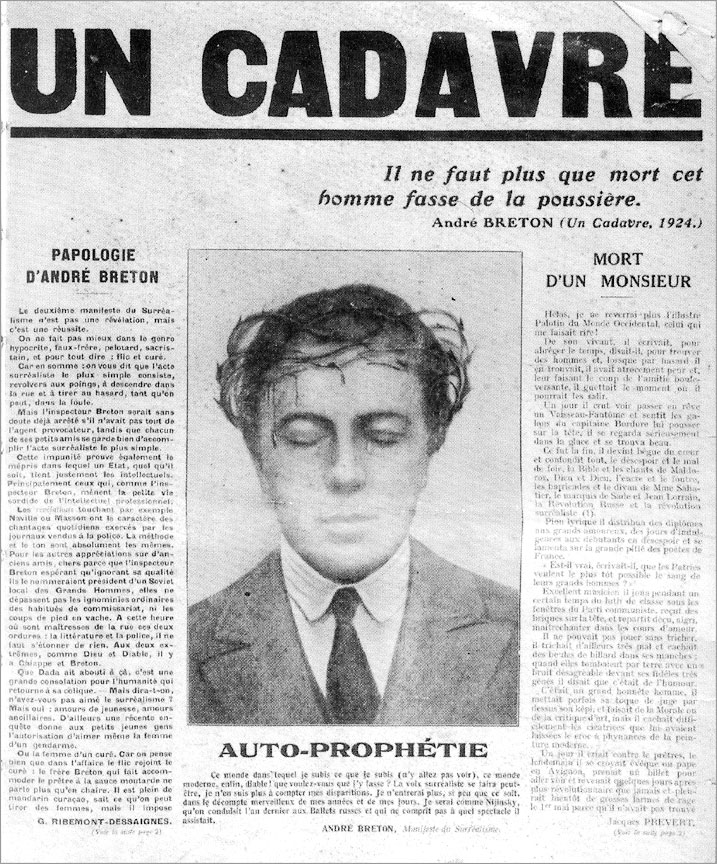

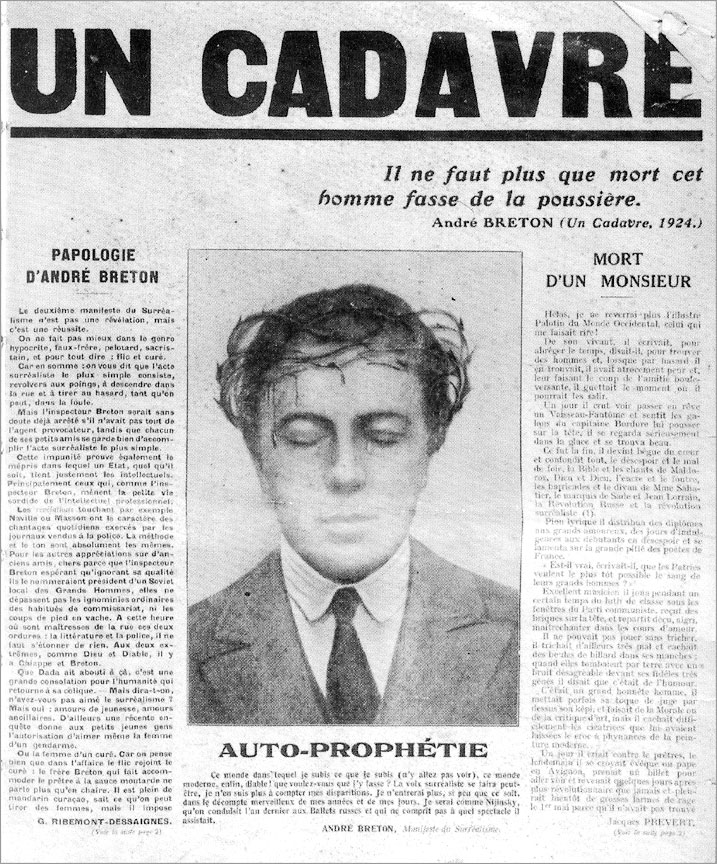

“Our modern art is … fashioned round a core of inner violence,” rejoined Bataille in a précis of his counter-surrealist manifesto, “…art that rather quickly presented a process of … destruction, which has been no less painful to most people than would have been the sight of the … destruction of a cadaver.” Bataille’s stinging invective against Breton, appropriately named Un cadavre [The Dead Body], attempted to ennumerate what the theoretician of excess had viewed as the folly of surrealism and the beginning of a new historical mysticism. Under Bataille’s philosophy, the spell of Fantômas was less a spectacle for the imagination and more a meditation on real crime and horror as a vivisection of the body—a historical landscape of grisly murders perpetrated by the likes of Christine and Lea Papin, con-man Henri Landru and medieval alchemist Gilles de Rais. The icon of Fantômas was transformed, in Bataille’s imagination, from a simple surrealist motif to a physical, historical and religious ‘Other’—something that could not or would not be named. For Bataille, Fantômas was not only a specter of literature but of society, preying on its fears of anarchy and ecstasy. The Surrealists had missed the point. The master of terror was not a representation of dreams or ideology but a literal convict marginalized by and terrorizing the populace.

It was this attraction to a world beyond the confines of the surrealist catechism – to the criminal and the transgressive – that caused the expulsion of poets and writers Desnos, Soupault, Artaud, Bataille, Raymand Queneau, Roger Gilbert-Lecomte and others from Breton’s ranks by the end of the 1920s.

“These young writers felt that society had lost the secret of its cohesion, and that here was precisely what the obscure, awkward and sterile efforts of poetic fever were seeking out,” wrote Bataille of the wave of surrealists who defected and soon joined his ranks. These so-called counter-surrealists appropriated the character of Fantômas to invoke a mysticism of immediate experience. Bataille’s arts review Documents, published from ’29-’30 and co-authored by fellow dissidents frequently included photo collages of carnival masks, anonymous cagoules—reminiscent of the hypersexualized image of Feuillade’s villain —close-ups of human anatomy and Starace’s Fantômas covers alongside critical essays analysizing ‘The Abattoir’, ‘The Eye’, and ‘The Sun’. For Bataille the evil tableau of Fantômas—and its Orphic cult of worship – transcended the mere philosophical and literary influence of Documents. To further explore the historical experiences of ritual and sacrifice he founded the controversial Collège de Sociologie at the Galeries du Livre, a tiny Parisian bookstore whose storeroom served as the school’s lectern. The “religious” wing of the college was altogether more secretive and abstruse in objective with an appropriate sobriquet, Acéphale [“headless”]. Proported to have included poet and writer Queneau, essayist Pierre Klossowski and sociologist Roger Caillois, who swore an oath of allegiance and absolute secrecy, the Acéphale conducted costumed rites, lamentations and mutiliations in the dark of night all for the inner experience of absolute negativity. Michel Fardoulis-Lagrange, a member of Acéphale spoke prophetically of the secret society’s philosophy: “Mystery had two faces, one turned outside and the other inside, the inside being tumult and chaos, and the outside the surpassing with a view to a new order. The ceremony took place outside while inside only waiting existed. On their own the open eyes made two absolute stains outside as well as inside.” His description betrays an uncanny resemblance to the violence and pageantry of Allain and Souvestre’s novels in the wake of Bataille’s critical mysticism.

In November 1933, fellow excommunicant Desnos used Fantômas as the inspiration for a theatre of cruelty-style production, La Complainte de Fantômas, performed on Radio Paris and featuring some 100 artists from opera singers to clowns, a score by composer Kurt Weill, and Artaud in the title role. Artaud would later develop this villanous alter ego to unimagined heights in the controversial radio play To Have Done With The Judgement of God.

***

Meanwhile, back in popular culture, the cinematic adventures of Fantômas continued after Feuillade’s five films. A 20-episode series directed by American Edward Sedgwick and produced by Fox Studios appeared in 1920, but a disagreement forced Fox to rename the serial Les Exploits de Diabolos during its French run and shorten the series number to twelve. Anthropologist and Hungarian expatriate Paul Fejos directed – and reinterpreted – a feature-length sound version of Fantômas in the early ’30s to little critical attention. On the advice of Jean Cocteau, Jean Marais starred in a three-part adaptation of Fantômas directed by André Hunebelle from ’64 to ’66, all of which recontextualized the original serials with a comedic, retro-futurist glamour that combined Carnaby Street style and MI5 espionage.

Dr Mabuse der Spieler (1922) - Fritz-Lang

While the Allain/Souvestre characters lived on in these homages, they shared very little in spirit with Feuillade’s unique metropolitan Gothicism. Rather than celebrating Fantômas as an avatar and archetype of the super-villain, filmmakers emphasized the camp qualities of the character so as to stand out in a market saturated with anti-heroes. The exception was Weimar auteur Fritz Lang’s underworld phantom, Doctor Mabuse, who would appear in a loose series of films produced from 1922 to 1960—Dr. Mabuse, The Testament of Doctor Mabuse and The 1000 Eyes of Doctor Mabuse— based upon Norbert Jacques’ pulp creation. An obvious descendant of Fantômas—but with characters and motifs explored in Metropolis and M and thus archetypally Langian – Mabuse was a criminal genius whose use of hypnosis and psychogenic fugue creates an army of followers who attempt to destroy the world.

With the ascension of the nouveau roman movement after the Second World War, the Allain and Souvestre novels found a new generation of literary enthusiasts. This so-called “new novel” resurrected the playful formal stylings of the serial and prefigured the use of pastiche and pop culture in postmodern art. It also extended the experimental subterfuge of surrealism and counter-surrealism in the face of its somber cousin, existentialism. Alain Robbe-Grillet, a central figure of the movement, was particularly inspired by the master villain in his stories of crime and intellectual ennui, having discovered Fantômas through his friendship with Rene Magritte, whose painting L’assassin menacé he used as a central pictorial trope in his film La Belle Captive. Robbe-Grillet’s work pointed to a larger fascination the literary underground had developed for the scandalous and gruesome fait-divers [“odd story”]—crime stories that had been printed in Parisian dailies since the 19th century. Essayist Roland Barthes, another prominent Fantômas devotee, believed the appeal of these criminal stories was in their “disturbing violence, accidents and irrational impulses below the surface of the everyday…We are thus in a world not of meaning but of signification, which is probably the status of literature, a formal order in which meaning is both posited and frustrated: and it is true that fait-divers is literature, even if this literature is reputed to be bad.” A better argument for the popularity of Fantômas has yet to be articulated so precisely. For the young artists maturing in the necropolis of World War II, Fantômas became an object of incomparable confusion and violence which they studied and referenced like a stigmata, an Iron Cross, a badge of dishonor.

René Magritte - Fantômas (1938)

In the same atmosphere of radical artistic change, filmmaking entered a new era and Feuillade began to gather a greater appreciation from young directors and movie-goers. Much as the nouveau roman was redefining the goal of the novel in the image of the fait-divers and the crime serial, cinema’s nouvelle vague [“new wave”] was incorporating images of gangsters, crime and urban ennui to its avant-garde palette. There was also a comparative cross-over in these artistic movements much as there had been between Allain and Souvestre’s Fantômas—the literary icon—and Feuillade’s film villain. While the nouveau roman sought to bring the formality and structures of film to literature, the nouvelle vague attempted to bridge modern literature’s dense textures and tropes with film: in the New Wave, authors like Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Duras were as central to the filmmaking process as Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais. It was in the seeds of this interdisciplinary collective that the work of Feuillade was resurrected from the charnel house of the silent-era and attained a new vogue.

Judex - Georges Franju (1963)

Much of Feuillade’s contemporary scholarship resulted from cineastes Georges and Henri Langlois who co-founded the Cinémathèque Française in 1937 and exhumed many of the director’s forgotten films from the vaults of Gaumont. Franju, a director in his own right, inspired as much by surrealism, the Grand-Guignol Theatre and Fantômas, produced a series of documentaries—The Blood of the Beast and Hotel des Invalides—that explored a similar poetics of violence. Many of his narrative films like Eyes Without a Face (famously described by Pauline Kael as “perhaps the most elegant horror film ever made”) and the comedic remake of Feuillade’s Judex owe much to Feuillade in style, tone and mise-en-scène. Franju would also make short documentaries on Marcel Allain and Georges Méliès during his career. Similarly, Feuillade devotee Alain Resnais combined the documentary/narrative style in his funereal Night and Fog which explores in uninterrupted panoramic shots the landscapes of Auschwitz in conjunction with archive footage of the Nazis’ atrocities. But it was Resnais’ classic meditations on psychotopology and memory—Hiroshima Mon Amour and Last Year at Marienbad—that most evoked Feuillade’s use of “depth of field” cinematography, claustrophobic and ever-shifting interiors and tones of sinister Gothicism.

“Feuillade is my god,” Resnais is famously quoted as saying. “I had always been a fan of the Fantômas dime thriller novels, but when I finally saw the films at the Cinemathèque in 1944, I learned from him how the fantastic could be more easily and effectively created in a natural exterior than in a studio. Feuillade's cinema is very close to dreams and is therefore perhaps the most realistic kind of all, paradoxical as this may sound."

***

In The False Judge, Feuillade’s fifth and final adaptation of Fantômas, released just months before France’s entrance into the War of 1914, the tone of the film slips noticeably into a somber and nihilistic dread. Opening with the sinister close-up of Rene Navarre dressed en cagoule and glaring at the viewer with the contented air of a condemned man, there is a repetitive inertia seemingly at play, casting the master villain as the perennial recidivist, the subject-hood of crime’s inexplicability, an aporia of meaning. In a startling legal and moral reversal of the grand narrative of Fantômas, The False Judge finds the former intentionally sprung from a Belgium prison and replaced by none other than Inspector Juve. With his new freedom secured, Fantômas returns to France where he promptly kills Judge Pradier in Saint-Calais and assumes his identity. Using his judicial and political position to increase his own coffers, Pradier connives to murder and extort thousands from the wealthy Marquise de Tergall. But when Fantômas’s apaches decide to conspire against him and steal his riches, he kills one of them in a cathedral bell, causing a shower of blood and jewels to cover a funeral party below. In a final ironic twist of Fantômas’ legal masquerade, the master of disguise preempts his own capture and execution by signing the release as Judge Pradier. As if prefiguring the moral indeterminancy of the Great War – when the “authority” of nationalism would be buried under mounds of the dead – Fantômas has not only eluded the Law from the outside but infiltrated its mechanism and transformed it from within like a cancer. Here the categories of good and evil are conflated to a zero-degree of meaning. The most insidious of Fantômas’ transgressions result from his dashing of reason and order to a shadow play, a dissimulation, an invitation to the absolute crime of ecstasy and excess.

While the cult surrounding Fantômas was always quintessentially French and his popularity beyond the country has never reached that same fever pitch, time has certainly insinuated the villain into the subconscious of the larger art world. In the nearly 100 years since Fantômas’s debut, he has been the object of sustained fascination among writers, artists and historians intent on uncovering the urban mythology of the 20th century. After more than 60 years without an English edition, Fantômas’s place in American letters was secured when a translation of the serial’s initial two volumes were released as a mass paperback by Ballantine Books in 1987 with an introduction by John Ashbery. After going out of print for more than a decade, the first volume was republished in 2006 by Penguin Classics. Black Coat Press, a California-based independent publisher established in 2003 by Jean-Marc Lofficier and dedicated to pulp fiction and French serials, has gone one step further, adapting the later editions of Allain as well as comic and cinematic interpretations of Fantômas. In only four years, Black Coat has introduced American readers to an entire genre of fait-divers and dime-store authors whose heroes and villains— like Arsene Lupin, Nick Carter and Rocambole —defined popular culture in Europe at the turn of the last century.

In 2000 Gaumont Studios and the Cinemathèque Française restored Feuillade’s five Fantômas films on a three DVD coffret with a new score by Jacques Champreux, additional images of the original movie posters, character biographies and interviews with Marcel Allain. British distribution company Artificial Eye has since issued a subtitled version of each film in their own box set, allowing English-speaking audiences their first glimpse of Fantômas in translation—and one of the first masters of cinema, Louis Feuillade. As David Thomson wrote, “...Fantômas is the first great movie experience, Feuillade the first director for whom no historical allowances need to be made. See him today and you still wonder…” The master of terror, it seems, continues to haunt our collective artistic fantasies, manipulating the sinister words and images of a century dedicated to the ecstasy and violence of his name.

Special thanks to Tav Falco, Victor Bockris, James Williamson, Steven M., Richard Pleuger and Lisa Poggiali.

THE SECRET MARK THAT FRENCH PULP VILLAIN FANTÔMAS LEFT ON THE 20TH CENTURY

Fantômas II - Juve Against Fantômas (1913) - Louis Feuillade

In 1911 the bourgeoning ‘industry’ behind French cinema was controlled by two powerful surnames: Pathé and Gaumont. Since the first exhibition of the Lumière Brothers’ cinematograph in 1895, rival inventors, filmmakers and producers had vied for control of the public’s imagination with this wonderful new device. The first successful auteur was Georges Méliès, a magician, carnival performer and artist, who released a fantastic series of truc d'arrêt [“trick films”] between 1896 and 1905, including Voyage to the Moon and The Impossible Voyage through his own Star Films production company. Méliès’ oeuvre was a constant source of fascination for a public raised on the exotica of the fairground and the prestidigitation of the Robert-Houdin Theatre, stage for France’s most celebrated magicians. But Star Films was quickly overextended, and eventually outmatched by the appearance of a film factory system and the construction of suburban cinémathèques at the behest of rivals Pathé Frères and Leon Gaumont. Through the prolific direction of Ferdinand Zecca and Alice Guy, in-house auteurs for each company, Pathé and Gaumont were able to out-perform Méliès at his own game and monopolize cinema.

Louis Feuillade came to Paris from Lunel, Herault, in 1898, and following a brief flirtation with the right-wing press, entered the Gaumont system as a writer in 1905. His interests in literature and vaudeville made him an ideal candidate for creating and adapting short scenarios to capture the public’s imagination. He replaced Alice Guy as artistic director within two years and began a directing career that would span two decades and over 800 films. Feuillade’s earliest, inchoate shorts were heavily indebted to Ferdinand Zecca and Méliès, utilizing elements of fantasy, magic and trick photography. Nearly 200 films later, Feuillade would find his own unique cinematic eye. According to the Cinemathèque Française’s Jacques Champreux, “The series with the most ambitious realism to date, La Vie telle qu’elle est, completed in 1911, marked a watershed moment in Feuillade’s career…and the first symptoms of his genius which would burst open with Fantômas.” But as Fantômas was not the first crime serial of the new century, neither would it be the cinematic debut of the noir genre. Zecca had directed L’Histoire d’un Crime (which depicts a murderer’s journey to the guillotine) and Victimes de l’alcoolisme, while Victorin Jasset had filmed a successful series of villain-versus-detective serials, including Zigomar contre Nick Carter (which set Léon Sazie’s criminal against the famous American pulp detective). Feuillade and Leon Gaumont were eager to make their own crime film in hopes of competing with Pathé. After negotiating the film rights for Fantômas, Feuillade commenced production at the Cite Elgé studios at Buttes Chaumont in early 1913. There, amidst the daily pandemonium of the burgeoning dream factory, he would craft some the greatest of cinema’s earliest masterpieces.

Buttes Chaumont Gaumont Studios

Glass-house studio at the Buttes Chaumont Gaumont Studios

“Although it is situated within Paris, on the side of the Chaumont hills, the factories of Gaumont have their own streets, trams, clothing stores, furniture depots, workshops for woodworking, of sculpture and painting, a printing works, a workshop for artists, théatres and…zoological gardens,” wrote a local reporter of the director’s workshop at the time. “Gaumont city is the city of the cinema.”

Feuillade’s technique was improvised play from the actors based on loose scenarios culled from the adapted volume. In What is Cinema?,Volume One, Cahiers du Cinema critic Andre Bazin explained Feuillade’s “writerly” technique as it proceeded throughout his directorial career:

Feuillade had no idea what would happen next, and filmed step-by-step as the morning's inspiration came…hence the unbearable tension set up by the next episode to follow and the anxious wait, not so much for the events to come but for the continuation of the telling, of the restarting of an interrupted act of creation…Both the author and the spectator were in the same situation, namely that of the King and Scheherazade; the repeated intervals of darkness in the cinema paralleled the separating off of the Thousand and One Nights. The “to be continued” of the true feuilleton [serial] as of the old serial films is not just a device extrinsic to the story. If Scheherazade had told everything at one sitting, the King, cruel as any film audience, would have had her executed at dawn. Both storyteller and film want to test the power of their magic by way of interruption to know the teasing sense of waiting for the continuation of a tale that is a substitute living which, in its turn, is but a but a break in the continuity of a dream.

Feuillade’s use of a stationary camera and limited close-up shots established a long, spatial surveillance of the mise-en-scène in which the characters of Fantômas, Juve and the supporting cast would maneuver like fluid props. This was no more brilliantly exhibited than in the very opening sequences of 1913’s Fantômas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine. Feuillade begins the first reel with a beautifully staged robbery at the hotel of Princess Sonia Danidoff, the camera following her continuously through the lobby, along each floor as she ascends in an elevator and into her suite. From behind the curtains the figure of Doctor Chaleck (actor Rene Navarre, to whom we are introduced in an opening montage) leaps upon her with an almost gallant step, demanding her silence with a flick of the finger, then proceeds to pocket her money and jewels. Before exiting he hands her a blank white business card and prays for her continued silence. Feuillade’s camera follows Chaleck as he descends floor by floor to the lobby, mugging and robbing a bellhop of his clothes in the interim. He is able to escape from the hotel undetected before Danidoff calls to report the heist. In a final moment of magic, Feuillade returns to the suite and employs a rare extreme close-up on the white card – in bold, black letters materializes the name “FANTÔMAS.”

Fantômas I - In the Shadow of the Guillotine (1913) - Louis Feuillade

In his use of fluid mise-en-scène, Feuillade was the first to perfect what Bazin called a realist’s la profondeur de champ [“depth of field”]. Rather than concentrate on the disintegration of character and object through a violent temporal redaction which moves the eye continuously, Feuillade maintains the space of the long-shot with every coordinate location being equally dense with possible significance…and ambiguity. As critic David Bordwell has remarked, “Seen from this standpoint, Feuillade becomes a forerunner of Welles, Wyler, Renoir, and the Italian Neorealists.” This use of depth accentuates the hidden caches and stalking villains who play in the chiaroscurist webs of presence and absence as they retreat between foreground and background. This constant shifting of space create multi-planar narratives within each filmed sequence and obscure the differences between characters, objects and mise-en-scène. In Fantômas these ‘planes’ of viewership often supersede the plotted action in their ability to inspire suspense and dread.

covers of Fantômas (1911) & Fantômas se venge! (orig. 1911) - Allain/Souvestre

Large portions of the original Allain/Souvestre debut had to be excised for the 54-minute film, including much of the portrayal of the French upper-class that might be considered the only element of social commentary present in the original text. In fact, Allain and Souvestre would attempt to insert transparent, Zola-inspired ribs at the haute-couture of the Right Bank aristocracy in each volume of Fantômas. But to Feuillade’s credit, he cut through the authors’ patronizing Naturalism and instead concentrated on the frequent masquerades of the master of crime as he entrusts himself to Lady Beltham and evades capture by Juve and Fandor. When Fantômas is finally apprehended and sentenced to death, Feuillade uses the brilliant sub-plot of Valgrand’s (an actor who has a striking resemblance to the prisoner) vain folly to spring the criminal from Santé at the last moment. In the closing moments of the film, a tortured Juve sits in his office at the precinct, imagining the elusive Fantômas disguised in black tie, top hat and mask appearing before him, teasing him to his feet only to dematerialize in his grip like a Méliès apparition.

The first Fantômas was released on 9 May 1913 at the massive Gaumont-Palace as a French cinematic event. As Jacques Champreux writes, “The triumph was immediate…An official statement published in the Petit Journal advertised the unbelievable figure of 80,000 spectators in a week…” But the theater-going public’s hunger for this cinema of crime did not often extend to the bourgeois circles who were increasingly looking to the American epic film—with its emphasis on characterization, plot development and pathos—as the standard-bearer for cinema-as-art. For them, Feuillade’s Fantômas was nothing more than a serial-come-to-life, a retrogressive display of violence and senseless thrills.

With each successive installment of the Fantômas films, Feuillade expanded both the visual language of the mise-en-scène and the spectacle of violence. In Juve Against Fantômas a foiled train robbery at Gare de Lyon hatched by Loupart—another disguise employed by Fantômas—and his newest mistress Joséphine-la-Pierreuse ends with a tragic derailment and explosion, killing hundreds of passengers. When Fantômas decides to murder Juve in the middle of the night, he releases a boa constrictor into his room to execute the deed. The inspector, who has learned of the plot but not of the method, covers his body with metal spikes. The ensuing bizarre melee between Juve and the snake is a model par excellence of sadomasochistic transgression. The psychosexual motif extends to the first glimpse of Fantômas en cagoule, covered from head to toe in a tight black bodysuit, a nihilist’s shroud which inverts the usual campish fashion and counterfeit costumery of the master of disguise. In one of the most disturbing images of the film, this creature swathed in his black raiment extends and writhes his body in a weird sign of victory after detonating a bomb meant to kill Juve and Fandor.

Fantômas II – Juve Against Fantômas (1913) - Louis Feuillade

Fantômas II – Juve Against Fantômas (1913) - Louis Feuillade

The Murderous Corpse finds Fantômas navigating through claustrophobic interiors to commit another series of murders and heists. The titular crux of the episode revolves around a particularly gory ruse whereby the villain has graduated from disguising his identity with clothes to human skin. His ensuing crimes are then attributed to a man whose mangled corpse has been left in the sewers. Princess Sonia Danidoff reappears just long enough to be re-victimized by Fantômas. Her fiancé, M. Thomery, is then lured by Lady Beltham to the hideout of Fantômas, where his newly acquired band of outsiders, all clothed en cagoule, kill the intruder in the film’s most infamous scene. Throughout the initial five reels of The Murderous Corpse the fate of Juve has been left unresolved, leaving Fandor on his own in tracking and capturing Fantômas. In fact, Juve has outmaneuvered his nemesis and infiltrated the inner circle only to reveal himself in the final reel in order to save Fandor. To heighten the sense of indeterminate spaces and psychotopological dread that infuses The Murderous Corpse Feuillade uses various odd angular shots and mutable stage sets. When Fantômas disappears into a hidden passageway at the film’s conclusion, it seems that Feuillade has reified the intense labyrinthine play to which he has subjected the viewer for nearly 90 minutes. With its emphasis on mise-en-scène, ambience and suspense, Feuillade’s lens invokes the dense phenomenologies of writers Jorge-Luis Borges, Maurice Blanchot and Raymond Roussel, arguably making The Murderous Corpse the most inventive and rewarding member of the serial.

Fantômas III - The Murderous Corpse (1913) - Louis Feuillade

In Fantômas Against Fantômas, suspicion is mounting that Juve himself is the nefarious villain. At the film’s opening, he is taken into custody and once again it’s up to Fandor to capture Fantômas and prove his friend’s innocence . Meanwhile, Fantômas employs another prop-bag of false identities—including the superannuated Pere Moche and the hilariously named American inspector Tom Bob—to stage a charity ball in his own honor. Aside from the beautiful sequence where three hooded figures enter Lady Beltham’s villa and only two exit, there is also a vividly gory moment in the first reel that has Tom Bob discovering a corpse hidden in an apartment crawlspace by way of a bleeding wall. The ongoing theme of ambiguous identity is further compounded as Fantômas foists another anatomical ruse upon Juve and nearly convinces the police chief of the inspector’s complicity. The narrative of Fantomas’ apaches – the criminal syndicate that surrounds him – is expanded here as is the number of the gang itself until it is quite pathologically portrayed to be an invisible world order of chauffeurs, bums, shopkeepers, streetwalkers, gendarmes and more, all carrying out Fantômas’ most quotidian whims and ensuring his freedom.

***

Allain and Souvestre together completed 32 volumes of the Fantômas serial, concluding with the villain’s death in The End of Fantômas. Their collaboration would certainly have continued had it not been for Souvestre’s untimely death during a Spanish influenza outbreak in the early winter of 1914. Allain would later resuscitate his most popular character and continued writing Fantômas sporadically from 1925 until 1963, completing 43 volumes in total and another 400 volumes comprising other serials. In an odd postscript, he would also marry Souvestre’s longtime girlfriend, Henriette Kistler, in 1926.

But it was not in the original compositions of Allain and Souvestre, nor in the film adaptations of Feuillade, that Fantômas would achieve his greatest notoriety and take on his most influential role. When the popularity of Fantômas was at its height just prior to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the master villain’s most important influence was measured neither in mass public reaction nor in bourgeois critical circles, but in the inspiration the serial had given to a new generation of poets, painters and philosophers living and working in the outskirts of Paris. It was here, amidst the renegade artistic movements blossoming in the cooperatives, cafés and galleries at the north and south ends of Paris, in the Montmartre workshop of Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire and at the bustling cafe tables of La Closerie des Lilas, La Coupole and Le Select, that Fantômas would become less entertainment and more a radical totem of twentieth-century psychic revolution. For the artists suspended above the void of total military destruction, Fantomas was recognized as a figure of sublime beauty and horror, a black-clad urban phantom, an oracle foretelling the grand-guignol of War. To these first generation groups, alternatively labeled Cubists, Fauvists, Surrealists, Dadaists and Futurists, the nightmarish visage of Fantômas—whether in dainty masquerade or hooded like an executioner—was the modern, industrial incarnation of 19th century-Europe’s various anti-heroes: Sade’s libertine, Maturin’s Melmoth and Lautréamont’s Maldoror.

Pablo Picasso, Moise Kisling and Paquerette at the Café de la Rotonde in Paris (1916) - photo by Jean Cocteau.

Here Fantômas, an objet d’art, transcends the social milieu of its origin and becomes reformatted according to the ideology of a new petit bourgeois art movement. For despite the representation of Fantômas as a renegade or iconoclast of middle-class law, the political backgrounds of his creators, Allain, Souvestre and Feuillade were entrenched in the established conservativism of the State. All three shared Catholic and monarchist sympathies that were quite opposed to the revolutionary ideology of the avant-garde. This gap in ideologies was indicative of the large spectra of political allegiances that dominated French, and particularly Parisian daily life, on the eve of the First World War. But its origins had been years in the making. From the humiliating loss of the Franco-Prussian war to Otto von Bismarck’s powerful German army, the bloody riots of the Paris Commune and the foundation of the Third Republic in 1871, France had been marked by a persistent national identity crisis propelled, in part, by a gaggle of rival political parties who vied for control of the government. “Ah, what a cesspool of folly and foolishness, what preposterous fantasies, what corrupt police tactics, what inquisitorial, tyrannical practices!” wrote Emile Zola of the state’s rampant injustices at the turn of the century. “What petty whims of a few higher-ups trampling the nation under their boots, ramming back down their throats the people’s cries for truth and justice, with the travesty of state security as a pretext.”

Zola’s political sentiments reached a crescendo during public scandals like the Dreyfus affair which exposed the factionalism and racism of a divided country. Falsely charged with treason and publicly cashiered from the army, Captain Alfred Dreyfus – a highly decorated soldier and Jew – became a cause célèbre for both conservatives and radicals. In response, party lines across the city tightened with an increasing intellectual intolerance. The Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO), the prominent socialist party mounted a major propaganda campaign against Action Française—led by the Catholic monarchist Charles Maurras—who had been largely responsible for inciting the public condemnation of Dreyfus. Maurras’ popularity rested on a prevalent French xenophobia which blamed the quatre états confédérés [“four confederated states”]—Jews, Protestants, Freemasons and immigrants —for the loss of the Prussian War and the rise in liberal ideology. For Maurras, these quatre états confédérés were proof that the effects of the Revolution had to be reversed if France were to be saved.

The Third Republic was also the age of the so-called apache. “A crime reporter for Le Journal, Arthur Dupin, had first used the term ‘apache’ to embellish his accounts of Paris street gang rivalry in 1902 and it soon became a code word for the urban criminal activity allegedly threatening French lives and property,” writes Richard Abel in The Thrills of Grande Peur: Crime Series and the Serials of the Belle Époque. As if to add insult to social injury, roving apaches, also known as mauvais garcons, would often adopt the sobriquet of the era’s most popular villain when committing their crimes, so that real robberies, muggings, and murders would often be blamed on a seemingly ubiquitous Fantômas. The phenomenon would recur so often that by the release of Feuillade’s next serial Les Vampires—a gothic tale of a murderous Parisian gang led by their sultry dominatrix, Irma Vep—the city government would institute a temporary ban on his films. Assassination, political intimidation and gang warfare were all common practices used on both the left and right to ensure territorial victory. In this environment the murder of SFIO leader and antimilitarist Jean Jaurès just days before mobilization against Germany had the very senseless fingerprint of Fantômas.

The first artistic flirtations with Fantômas came with Apollinaire’s July 1914 review of the Allain/Souvestre serial in the literary review Mercure de France, where the perpetually overzealous writer baptized the work an “…extraordinary novel, full of life and imagination...from the imaginative standpoint, Fantômas is one of the richest works that exist.” If this was the first call for the apotheosis of the serial character, it would certainly not be the last. Apollinaire’s absolutist and inflammatory declaration incited his fellow artists from Montmartre and Montparnasse to match his loquacious prose. In an August edition of Les Soirées de Paris, Apollinaire collaborator Maurice Raynal wrote of Feuillade’s Fantômas, “And now, dare I or don’t I? Well, take courage and trust in the grace of God. Now… Fantômas! What nobility! What beauty! It’s one of those things that stuns you; its serene majesty, like inimitable brilliance, leaves you breathless, dazed and mute…It is like the best of Hugo, and more beautiful in fact!” In Max Jacob’s 1916 collection Le Cornet à dés [The Dice Cup], the Montmartre eccentric includes a playful lyric of two gourmands’ unlikely encounter with the master villain in “Encore Fantômas.” Soon other outspoken writers would add their kudos, throwing their hats into an ever-widening ring of “Friends of Fantômas.” “Absurd and magnificent lyricism,” claimed the cravat-and-laced dandy Jean Cocteau. “The modern Aeneid” countered poet and essayist Blaise Cendrars. Even James Joyce was a follower, penning a typically Joycean neologism “Enfantomastic” to describe his adulation.

Fantômas (1915) - Juan Gris

Painters and sculptors experimenting in the burgeoning cubist style found in Fantômas a dark, foreboding icon they could insert, scatter and deconstruct upon the canvas using the ‘poetic’ methods of collage and decoupage. Juan Gris’ 1915 painting Fantômas (Pipe and Newspaper) centered on the bricolage of a café and included a copy of the serial novel among the scattered objects. Yves Tanguy, a friend of surrealist poet Jacques Prévert and an eventual ally of Andre Breton, produced an homage to the master of crime in 1925 using the angular, biomorphic styles of Giorgio de Chirico and Salvador Dali. (“Even in an atypical ‘literary’ painting such as this, no very accurate reading is possible,” wrote John Ashbery of the piece in 1974. “Space and perspective are methodically distorted; it is impossible to gauge distances by the size of the figures, and there is some iconography…which seems not to relate to the story of Fantômas. The stage seems set for the radical transformations which will very shortly sweep it almost bare.”) In a 1966 article for Film Commentary entitled “Early Surrealist Expression in the Film”, Georges Sadoul recounts in an interview with critic Toby Mussman, “…how he, Jacques Prévert, Yves Tanguy, and [writer] Raymond Queneau would spend whole evenings discussing their knowledge of the various episodes of the Feuillade serials….”

Belgian expatriate René Magritte employed Fantômas as a subject throughout his work in the ’20s. In his 1926 L’assassin menacé (The Menaced Murderer) Magritte reproduces a famous “depth of field” image from The Murderous Corpse where two members of Fantômas’ gang lie in wait against a doorway, preparing to commit their nefarious deed. Beyond the cinematic images of Rene Navarre’s character, Magritte used Gino Starace’s serialized covers to great effect. For example, 1928’s Le barbare (The Barbarian) is a trompe l’oeil that uses a Starace-inspired Fantômas camouflaged amid the tessellations of a brick wall. And in 1943’s Le retour de flamme (The Return of the Flame), Magritte uses Starace’s iconic landscape of Paris with the masked villain stepping over the Eiffel Tower. So immersed was Magritte in the novels and Feuillade films that he would once tell an interviewer, “I am Fantômas.”

Fantômas III - The Murderous Corpse (1913) - Louis Feuillade

L'assassin menacé (1926) - René Magritte

The first legitimate cult dedicated to the master of crime appeared in Montmartre in 1913. Despite its impressive and oblique title, the “Society of Friends of Fantômas” (SAF), as it was initially called by founder Apollinaire, was no more than a loose cadre of artistic apaches who lacked any central manifesto or political agenda. But as a precursor to Dada and the Surrealist movements by more than five years, the SAF proved essential as the initial rebel yell for the young, dispossessed artists living in the northern banlieue. And Fantômas was to be their totem.

The foundation of the SAF also lied in Apollinaire’s personal connections with the Cubist school established by Picasso and Georges Braque (also SAF members) between 1908 and 1911. The SAF headquarters was located at Picasso’s workshop near the Sacré-Cœur Basilica and the Moulin Rouge, the infectious center of Montmartre’s bohemian enclave. Thousands of poets, painters, musicians, critics, dancers, grifters, thieves and flaneurs called the neighborhood between the Butte Montmartre and the Rue Pigalle their home and stomping ground. It was here that the poet/dandy Jean Cocteau would meet Picasso and form an immediate artistic bond that would last nearly half a century. It would also provide Cocteau entrée into the underground art world inhabited by composer Erik Satie, Russian director Serge Diaghilev and Blaise Cendrars. So wild and licentious were the days and nights of Montmartre, with its cabarets, brothels, saloons and opium dens, that it singularly defined the French term demi-monde (“underworld”) as a nexus of crime and artistic invention. But its riotous extremes were not limited to the northern end of Paris. In 1911, when Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was pilfered from The Louvre in what the police considered an “inside job”, the conspiracy led straight from the Seine to Picasso’s workshop. Apollinaire and Picasso were both arrested on suspicion and hauled in front of a magistrate at the Palais de Justice for questioning. They were eventually exonerated for lack of evidence.

If the artists of the SAF romanticized a certain conceptual violence which they grafted onto the page or canvas as an act of cultural rebellion, the dizzying bloodshed of war may have come as a bitter reward indeed. With the arrival of la grande guerre in August 1914, many of Montmartre’s artists and poets were mobilized on the Eastern front or fled Paris to avoid conscription. Picasso was drafted by the military to produce large simulated canvases of French soldiers and foliage to confuse the German invaders in the trenches. Cocteau was a medic on the Belgian front but fortunately shuttled back and forth to Paris regularly and saw little action by the war’s end. Others were not so fortunate. Apollinaire suffered a massive head wound from flying shrapnel in 1916 and was decommissioned shortly thereafter. The complications from the hematoma would cause the poet severe pain and dizzy spells until his death in 1918. Fernand Léger, another cubist-inspired painter, nearly died during a mustard gas attack at Verdun. Poet André Breton spent the war caring for patients in a neurological ward in Nantes. There he would meet one of his greatest Surrealist inspirations, Jacques Vaché, a writer and Pere Ubu eccentric who would tragically kill himself in 1919. Other young poets and painters, like Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia left for America before the war began, outraging many of the pro-French artists who were determined to fight for their homeland.

_at_the_Th%C3%A9%C3%A2tre_du_Ch%C3%A2telet%2C_Paris%2C_1917%2C_Lachmann_photographer.jpg)

Pablo Picasso and scene painters sitting on the front cloth

for Léonide Massine's ballet Parade, staged by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes

at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris (1917) - photo : Lachmann

In spite of the massive physical and psychological destruction incurred in Calais and the Ardennes in 1916-17, life among the Montmartre vanguard continued in Paris at a fever pitch. One of the most notorious cultural events to echo across the city during the height of the war came with the performance of Parade at the Théatre du Chatelet. Purportedly developed by Cocteau in response to dance director Serge Diaghilev’s daring words “Etonne-moi!” [“Astonish me”], Parade was a carnivalesque spectacle filled with jugglers, acrobats and ragtime dancers. Premiering in May 1917 with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, music by Erik Satie and stage sets by Picasso—all members of the SAF—Parade was one of the earliest synergistic collaborations of the Cubists and surrealists. In fact, the term surrealism was first coined in the performance playbill by a crippled Apollinaire who wrote that Parade was “une sorte de surréalisme”. So divisive was its debut that Parade is often compared in notoriety to the 1913 performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring which caused riots across Paris. “If it had not been for Apollinaire in uniform,” wrote Cocteau of the evening, “with his skull shaved, the scar on his temple and the bandage around his head, women would have gouged our eyes out with hairpins.” The imagined scene of mayhem recalls nothing short of the most violent purges of Fantômas.

La révolution surréaliste (March 1928 - Dec. 1929)

The predominantly French surrealism movement was developing in tandem with its more outrageous Swiss cousin, Dada. Dada’s first public recitation had come in July 1916 at Zurich’s infamous Cabaret Voltaire and resident theoretician Tristan Tzara published his earliest manifesto two years later. When the regulars of the Voltaire dispersed at the conclusion of the War, Tzara traveled to Paris where he discovered compatriots Apollinaire and Breton waiting anxiously for his arrival. But it was Breton and not Tzara who would take the reins from Apollinaire after his untimely demise in the influenza pandemic of November 1918. Breton had already begun to amass a newer generation of young writers and aesthetes and, with their support, easily slipped into the ceremonial position left vacant at Apollinaire’s death. In the following year Breton, Aragon and Soupault debuted their own ‘surrealist’ magazine Littérature and a collaborative novel Les Champs Magnétiques [The Magnetic Fields] – published in 1920 – was the first piece credited to the automatic writing technique and officially licensed by Breton as surréalisme. “Surrealism will usher you into death, which is a secret society,” wrote Breton in 1924’s Le Premier Manifeste du Surréalisme. “It will glove your hand, burying therein the profound M with which the word Memory begins.” In a profound evocation of the SAF and the mysterious violence of its idol, the proported tenets of surrealism claimed its raison d’etre to be a celebration of the le merveilleux quotidien [“the everyday marvellous”] and its individual corollate, the ‘un’conscious. What Dada had instigated as a reactive, anti-Art campaign against the traditional, bourgeois valuations of aesthetics and class, surrealism had expanded upon with a neoteric regimen of Freudian analysis, Hegelian dialectics and radical politics. Breton’s infectious distillation of art and philosophy might well have driven those unaffiliated artists around him to join his ranks in the beginning – including artists from the rue Blomet and the rue du Château and the so-called Grand Jeu – but it was this very rigid idealism that would make of them mavericks. Despite what he had claimed as a surrealist aphorism par excellence – “The exquisite corpse drinks the new wine…” – Breton’s celebration of the narrative of the body was tempered with an increasing dependence on psychoanalysis and Marxist politics. His descriptions of the marvellous had always favored chance and random juxtaposition, neurosis and the dream-state, but refused to negotiate the more sinister categories of excess and atrocity – desire, violence and death. When Breton allied himself with the French Communist Party in ’27 amid an ultra-militarized left the focus of surréalisme became a political rather than aesthetic Revolution. All notions of literary and artistic decadence, primitivism and hermeticism were excised and condemned within the group.